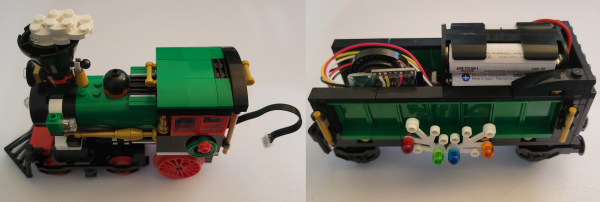

The Toniebox is a toy that plays stories and songs for kids to listen to. Audio content can be changed by placing different NFC enabled characters that magnetically attach to the top of the toy. It can play audio via its built-in speaker or through a wired headphone connected to the 3.5 mm stereo jack. Using the built in speaker could sometimes be quite an irritant, especially if the parents are in “work from home” mode. And wired headphones are not a robust alternative, specially if the kid likes to wander around or dance while listening to the toy. We guess the manufacturers didn’t get the memo that toddlers and cables don’t mix well together. Surprisingly, the toy does not support Bluetooth output, so [g3gg0] hacked his kids Toniebox to add Bluetooth audio output.

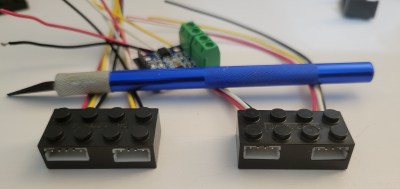

[g3gg0] first played with the idea of transmitting audio via an ESP32 connected to the I²S interface, running a readily available A2DP library. While elegant, it is a slightly complex and time consuming solution. Using the ESP32 would also have affected the battery life, given the ESP32’s power hungry nature. Continue reading “CUTTING CABLES CURES TANGLED CORD CHAOS”