According to [Charles Q. Choi], a new study indicates that grooves in the hydrogen fuel cells used to power vehicles can improve their performance by up to 50%. Fuel cells are like batteries because they use chemical reactions to create electricity. Where they are different is that a battery reacts a certain amount of material, and then it is done unless you recharge it somehow. A fuel cell will use as much fuel as you give it. That allows it to continue creating electricity until the fuel runs out.

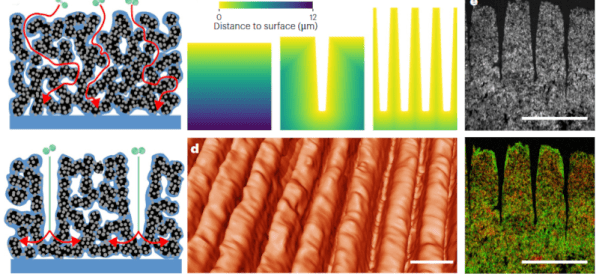

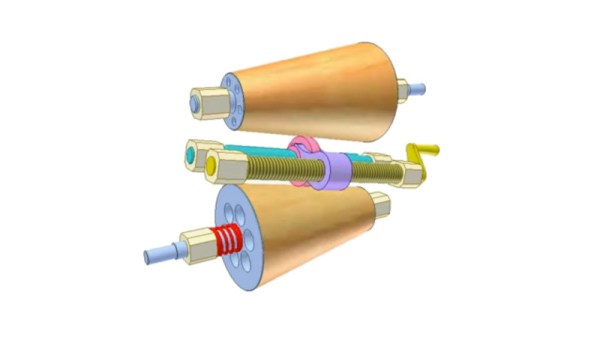

Common hydrogen fuel cells use a proton exchange membrane — a polymer membrane that conducts protons to separate the fuel and the oxidizer. You can think of it as an electrolyte. Common fuel cells use an electrode design that hasn’t changed in decades. The new research has catalyst ridges separated by empty grooves. This enhances oxygen flow and proton transport.

Conventional electrodes use an ion-conducting polymer and a platinum catalyst. Adding more polymer improves proton transport but inhibits oxygen flow. The grooved design allows for dense polymer on the ridges but allows oxygen to flow in the grooves. In technical terms, the proton transport resistance goes down, and there is little change in the oxygen transport resistance.

The grooves are between one and two nanometers wide, so don’t pull out your CNC mill. The researchers admit they had the idea for this some time ago, but it has taken several years to figure out how to fabricate the special electrodes.