Many low-cost wireless temperature and humidity sensors use a 433 MHz transmitter to send data back to their base stations. This is a great choice for the manufacturer of said devices because it’s simple and the radios are cheap, but it does limit what we as the consumer can do with it a bit. Generally speaking, you won’t be reading data from these sensors on your computer unless you’ve got an SDR device and some experience with GNU Radio and reading the Nexus protocol.

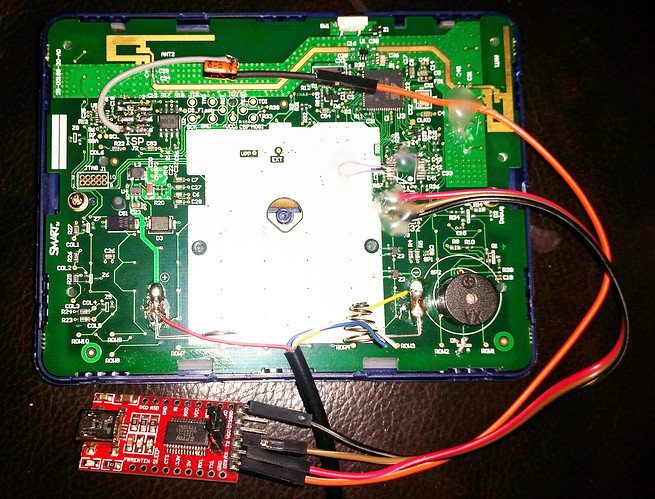

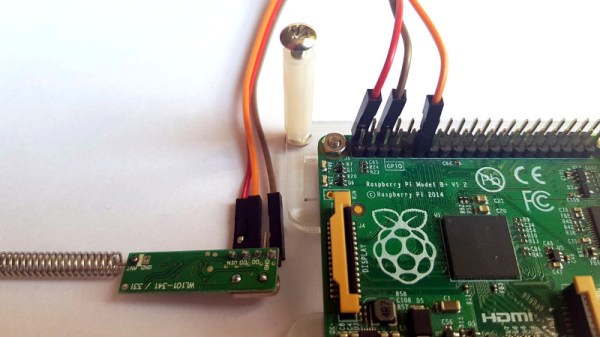

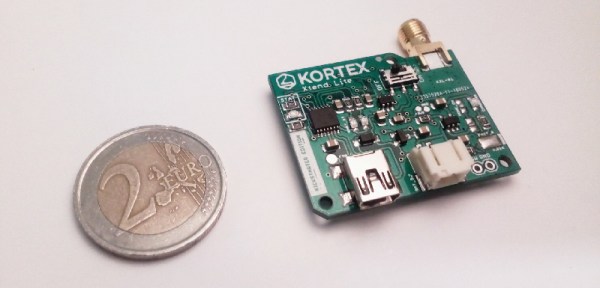

But [Aquaticus] has developed a very comprehensive piece of software that should make integrating these type of sensors into your home automation system much easier, as long as you’ve got a spare Raspberry Pi lying around. Called nexus433, it uses a cheap 433 MHz receiver connected to the Pi’s GPIO pins to receive data from environmental sensors using the popular Nexus communication protocol. A few known compatible sensors are listed in the project documentation, one of which can be had for as little as $5 USD shipped.

But [Aquaticus] has developed a very comprehensive piece of software that should make integrating these type of sensors into your home automation system much easier, as long as you’ve got a spare Raspberry Pi lying around. Called nexus433, it uses a cheap 433 MHz receiver connected to the Pi’s GPIO pins to receive data from environmental sensors using the popular Nexus communication protocol. A few known compatible sensors are listed in the project documentation, one of which can be had for as little as $5 USD shipped.

In addition to publishing the temperature, humidity, and battery level values from the sensors to MQTT, it even tracks connection quality for each individual sensor and when they go on and offline. To be sure, this is no simple hack. In nexus433, [Aquaticus] has created a mature Linux service with enough flexibility that you shouldn’t have any problems working it into your automation setup, whether it’s Home Assistant or something you’ve put together yourself.

We’ve seen a number of home automation hacks using these ubiquitous 433 MHz radios, from controlling them with an ESP8266 to hacking a popular TP-LINK router into a low-cost home automation hub.

Over the years, a number of gadgets with BLE have popped up such as the LightBlue Bean, BLE Beacons as well as quadcopters like the FlexBot that rely on BLE for communication. Android or iOS apps are the predominant method of talking to these wonderful gadgets though there are alternatives.

Over the years, a number of gadgets with BLE have popped up such as the LightBlue Bean, BLE Beacons as well as quadcopters like the FlexBot that rely on BLE for communication. Android or iOS apps are the predominant method of talking to these wonderful gadgets though there are alternatives.