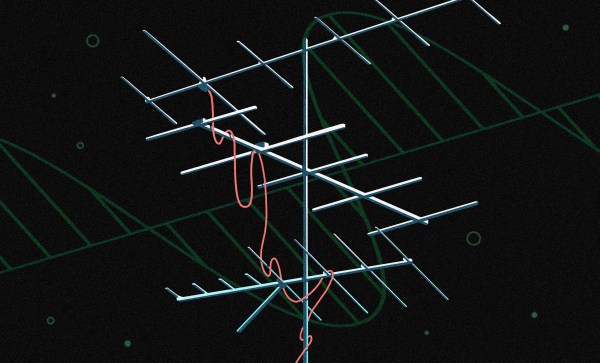

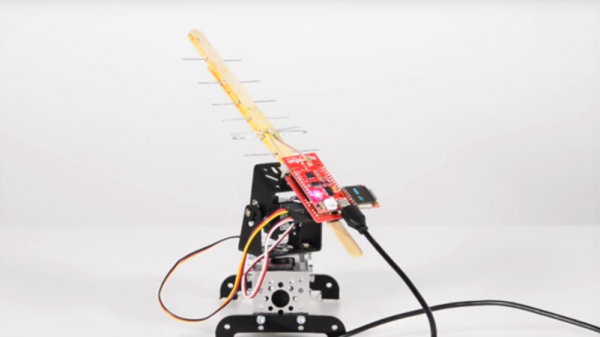

If you happened to look up during a drive down a suburban street in the US anytime during the 60s or 70s, you’ll no doubt have noticed a forest of TV antennas. When over-the-air TV was the only option, people went to great lengths to haul in signals, with antennas of sometimes massive proportions flying over rooftops.

Outdoor antennas all but disappeared over the last third of the 20th century as cable providers became dominant, cast to the curb as unsightly relics of a sad and bygone era of limited choices and poor reception. But now cheapskates cable-cutters like yours truly are starting to regrow that once-thick forest, this time lofting antennas to receive digital programming over the air. Many of the new antennas make outrageous claims about performance or tout that they’re designed specifically for HDTV. It’s all marketing nonsense, of course, because then as now, almost every TV antenna is just some form of the classic Yagi design. The physics of this antenna are fascinating, as is the story of how the antenna was invented.