If your robot has outgrown a Raspberry Pi and only the raw computing power of an x86 motherboard will suffice, you are likely to encounter a problem with its interfaces. The days of ISA cards are long gone, and a modern PC is not designed to easily talk to noisy robot hardware. Accessible ports such as USB can have interfaces connected to them, but suffer from significant latency in the process.

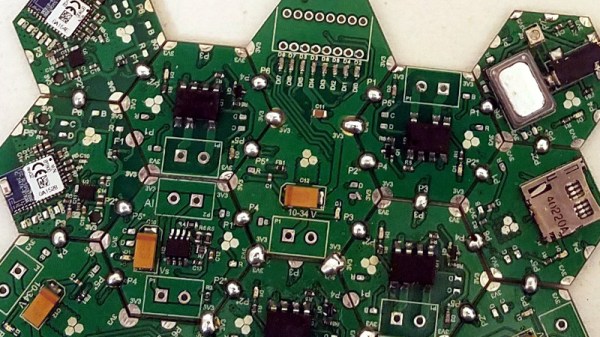

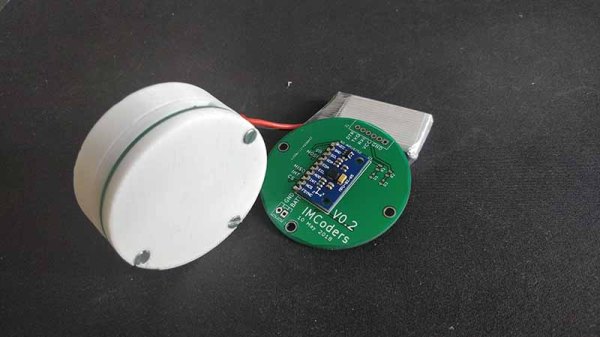

A solution comes from ROPS, or Robot on a PCI-e Stick, a card that puts an FPGA on a blazing-fast PCI-e card that provides useful real-world interfaces such as CAN and RS485 and a pile of I/O lines as well as an IMU, barometer, and GPS. If you think you may have seen it before then you’d be right, it was one of the first-round winners of the Open Hardware Design Challenge. They’re very much still at the stage of having an FPGA dev board and working out the software so there aren’t any ROPS boards to look at yet, but this is a project that’s going somewhere, and definitely one to watch.