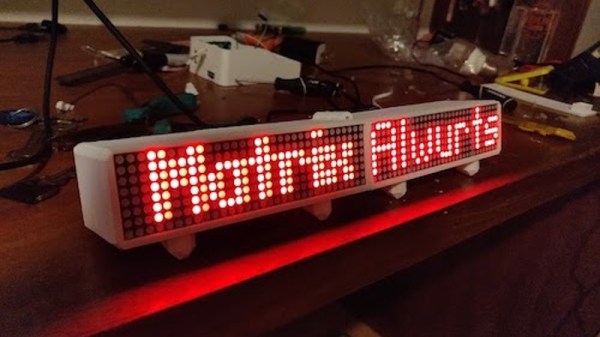

Over the years we’ve seen countless ways of displaying the current time, and judging by how many new clock projects that hit the tip line, it seems as though there’s no end in sight. Not that we’re complaining, of course. The latest entry into the pantheon of unusual timepieces is this ESP32-powered desk clock from [Alejandro Wurts] that features a folding LED matrix display.

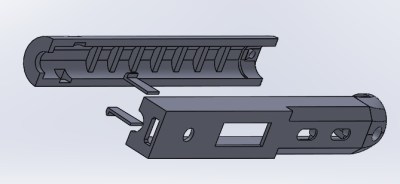

The clock uses eight individual 8 x 8 LED arrays contained in a 3D printed enclosure that hinges in the middle. When opened up the clock has a usable resolution of 8 x 64, and when its folded onto itself the resolution becomes 16 x 32.

The clock uses eight individual 8 x 8 LED arrays contained in a 3D printed enclosure that hinges in the middle. When opened up the clock has a usable resolution of 8 x 64, and when its folded onto itself the resolution becomes 16 x 32.

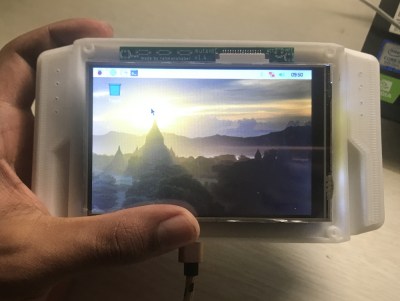

This variable physical resolution allows for alternate display modes. When the hardware detects that its been folded into the double-height arrangement, it goes into a so-called “Big Clock” mode that makes it easier to see the time from a distance. But while in single-height mode, there’s more horizontal real estate for adding the current temperature or other custom data. Eventually [Alejandro] wants to use MQTT to push messages to the display, but for now it just shows his name as a placeholder.

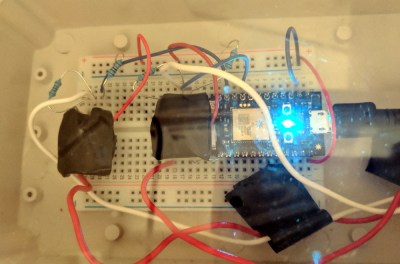

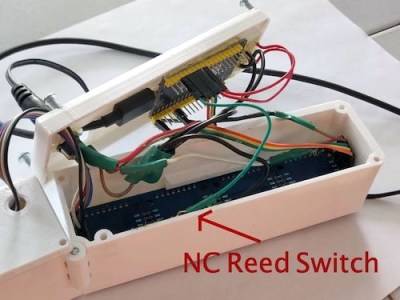

The key to the whole project is the hinged enclosure and the reed switch used to detect what position it’s currently in. Beyond that, there’s just an ESP32 an some clever code developed with the help of the MD_Parola library written for MAX7219 and MAX7221 LED matrix controllers. [Alejandro] has published the code for his clock, which should be helpful for anyone who’s suddenly decided that they also need a folding LED matrix in their life.

Now if the ESP32 LED matrix project you have in mind requires full color and high refresh rates, don’t worry, we’ve got a solution for that.

Continue reading “An ESP32 Clock With A Transforming LED Matrix”