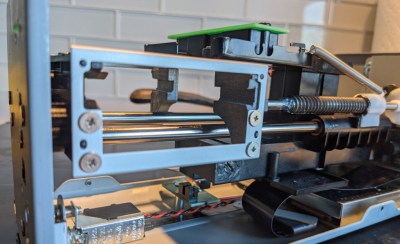

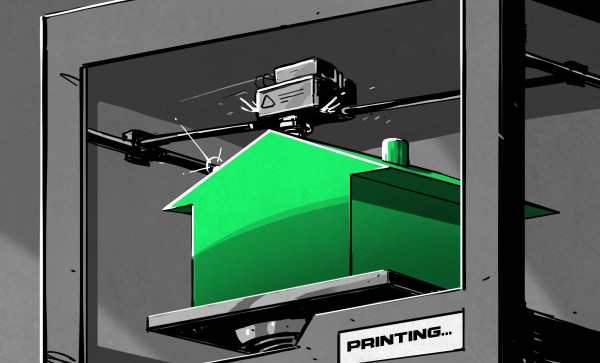

Many of the hardware orientated hackers among us will likely have been following along with the story of [Stephen Hawes] and the Lumen pick-and-place project but kind of waiting a bit for the project to mature some more before maybe taking the plunge and ordering a kit. One reason for this might be that whilst the basic machine design is there and working, the tape feeders did need a fair bit of work, and a lack of usable feeders does not make a great PnP machine. [Stephen] has been working on a newer design that addresses some of the identified shortcomings, and has started documenting his progress (video, embedded below) along the way.

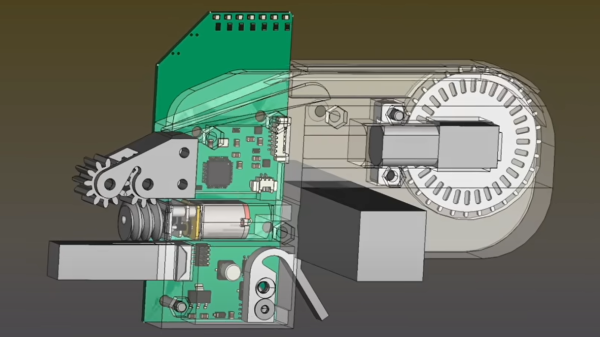

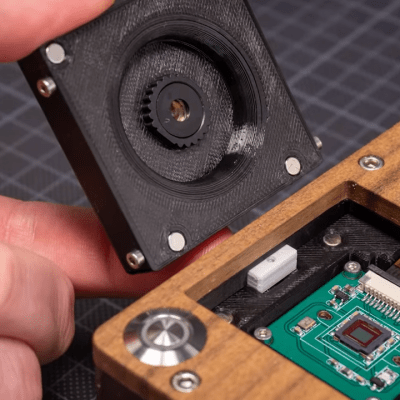

Gone is the PCB-based ‘case’, reverting back to a 3D printable affair and a much smaller PCB. After flip-flopping a bit between different geared DC motors, [Stephen] settled back on the original, smaller unit, which after a wee spot of hacking, was convinced to accept an optical encoder stripped from another unit, and this proved that it was indeed more than up to the tape-advancement duty. The reason for this change was physical size — the original motor resulted in an assembly 38mm wide — this limited the number for feeders on the front rail to barely eleven units. This is not really enough, but with the narrower assembly, the width is reduced to 15.5mm allowing 27 feeders to snuggle together on the rail, and that should make the machine much more usable.