Telling somebody that you’re going to make their dreams come true is a bold, and potentially kind of creepy, claim. But it’s one of those things that isn’t supposed to be taken literally; it doesn’t mean that you’re actually going to peer into their memories, extract an idea, and then manifest it into reality. That’s just crazy talk, it’s a figure of speech.

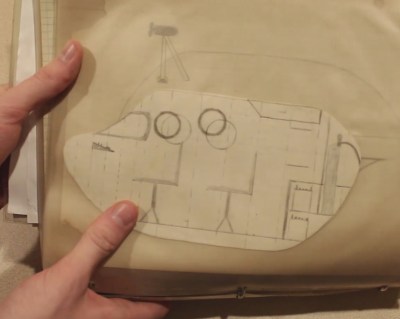

As it turns out, there’s at least one person out there who didn’t get the memo. Remembering how his father always told him about the elaborate drawings of submarines and rockets he did as a young boy, [Ronald] decided to 3D print a model of one of them as a gift. Securing his father’s old sketchpad, he paged through until he found a particularly well-developed idea of a personal sub called the CURV II.

The final result looks so incredible that we hear rumors manly tears may have been shed at the unveiling. As a general rule you should avoid making your parents cry, but if you’re going to do it, you might as well do it in style.

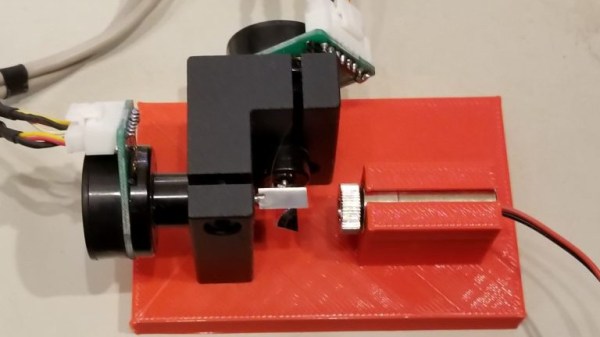

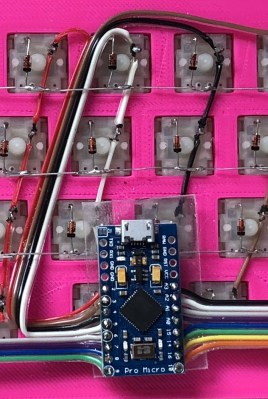

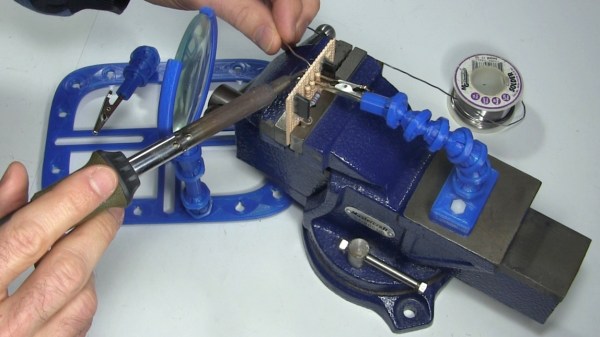

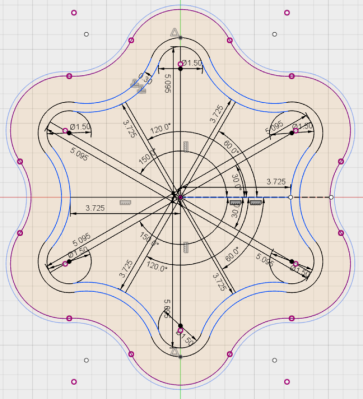

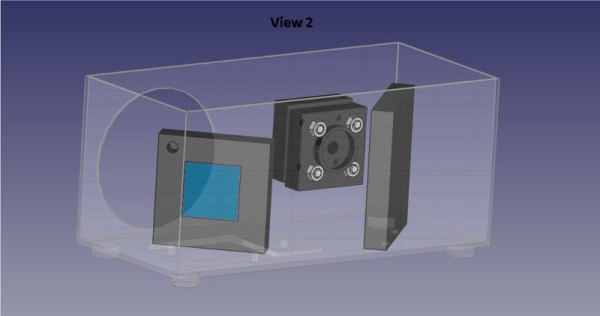

Considering that his father was coming up with detailed schematics for submarines in his pre-teen days, it’s probably no surprise [Ronald] has turned out to be a rather accomplished maker himself. He took the original designs and started working on a slightly more refined version of the CURV II in SolidWorks. Not only did he create a faithful re-imagining of his father’s design, he even went as far as adding an interior as well as functional details such as the rear hatch. Continue reading “3D Printing Brings A Child’s Imagination To Life”