The Switch is the new hotness and everyone wants Nintendo’s new portable gaming rig nestled in a dock next to their TV, but what about Nintendo’s other portable gaming system? Yes, the New Nintendo 3DS can get a charging dock, and you can 3D print it with swappable plates that make it look like something straight out of the Nintendo store.

[Hobby Hoarder] created this charging dock for the New Nintendo 3DS as a 3D printing project, with the goal of having everything printable without supports, and able to be constructed without any special tools. Printing a box is easy enough, but the real trick is how to charge the 3DS without any special tools. For this, [Hobby Hoarder] turned to the small charging contacts on the side of the console. All you do is apply power and ground to these contacts, and the 3DS charges.

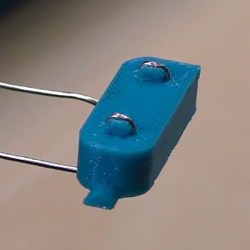

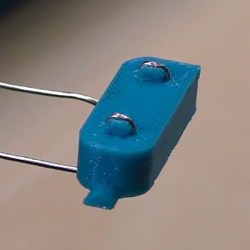

Normally, adding contacts requires pogo pins or hilariously expensive connectors, but [Hobby Hoarder] has an interesting solution: just add some metal contacts constructed from LED leads or paper clips, and mount it on a spring-loaded slider. A regular ‘ol USB cable is scavenged, the wires stripped, and the red and black lines are attached to the spring-loaded slider.

Normally, adding contacts requires pogo pins or hilariously expensive connectors, but [Hobby Hoarder] has an interesting solution: just add some metal contacts constructed from LED leads or paper clips, and mount it on a spring-loaded slider. A regular ‘ol USB cable is scavenged, the wires stripped, and the red and black lines are attached to the spring-loaded slider.

There is a slight issue with the charging voltage in this setup; the 3DS charges at 4.6 Volts, and USB provides 5 Volts. If you want to keep everything within exacting specs, you could add an LDO linear regulator, but there might be issues with heat dissipation. You could use a buck converter, but at 0.4 Volts, you’re probably better off going with the ‘aaay yolo’ theory of engineering.

[Hobby Hoarder] produced a few great videos detailing this build, and one awesome video detailing how to print multicolored faceplates for this charging dock. It’s an excellent project, and a great example of what can be done with 3D printing and simple tools.

Continue reading “3D Print That Charging Dock For Your 3DS” →