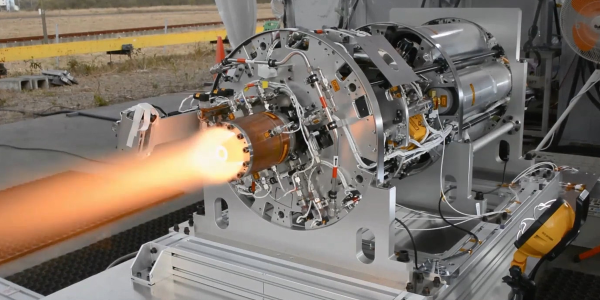

Go back a generation of development, and excepting the shuttle-derived systems, all liquid rockets used RP-1 (aka kerosene) for their first stage. Now it seems everybody and their dog wants to fuel their rockets with methane. What happened? [Eager Space] was eager to explain in recent video, which you’ll find embedded below.

At first glance, it’s a bit of a wash: the density and specific impulses of kerolox (kerosene-oxygen) and metholox (methane-oxygen) rockets are very similar. So there’s no immediate performance improvement or volumetric disadvantage, like you would see with hydrogen fuel. Instead it is a series of small factors that all add up to a meaningful design benefit when engineering the whole system.

Methane also has the advantage of being a gas when it warms up, and rocket engines tend to be warm. So the injectors don’t have to worry about atomizing a thick liquid, and mixing fuel and oxidizer inside the engine does tend to be easier. [Eager Space] calls RP-1 “a soup”, while methane’s simpler combustion chemistry makes the simulation of these engines quicker and easier as well.

There are other factors as well, like the fact that methane is much closer in temperature to LOX, and does cost quite a bit less than RP-1, but you’ll need to watch the whole video to see how they all stack up.

We write about rocketry fairly often on Hackaday, seeing projects with both liquid-fueled and solid-fueled engines. We’ve even highlighted at least one methalox rocket, way back in 2019. Our thanks to space-loving reader [Stephen Walters] for the tip. Building a rocket of your own? Let us know about it with the tip line.