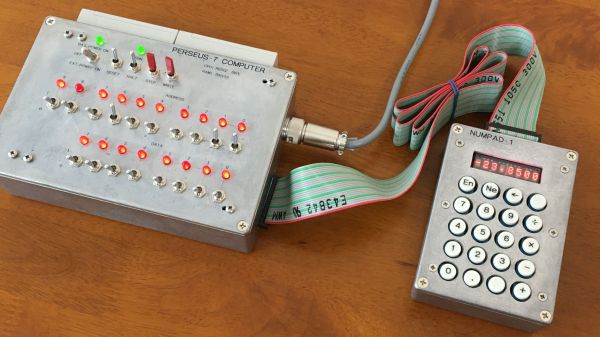

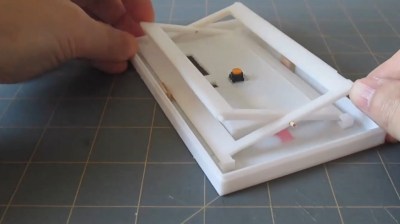

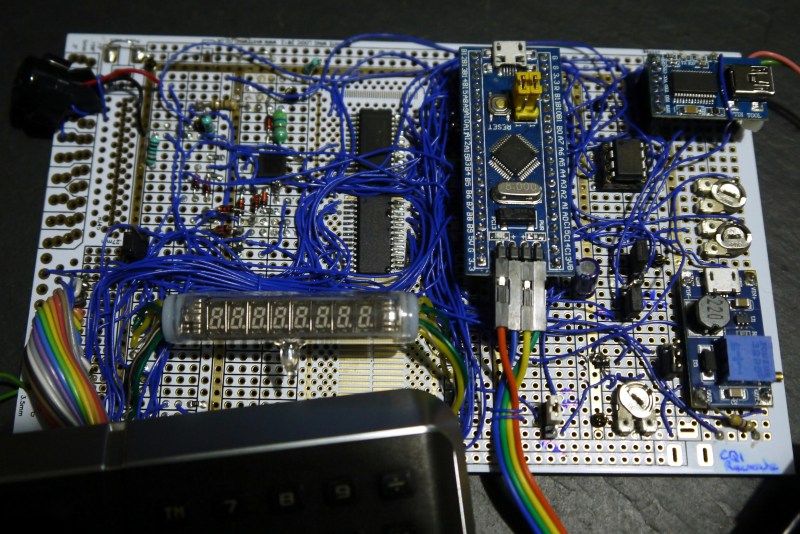

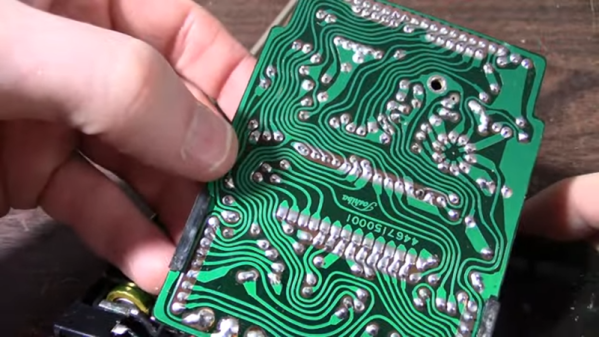

[Mitsuru Yamada] states that one of the goals for this 6502 computer build was to make it strong enough to survive real-world usage. In that regard alone we’d call this a success; the die-cast aluminum enclosures used are a little blast from the past and lend a nice retro industrial look to the project. The main chassis of the computer fairly bristles with LEDs and chunky toggle switches for setting the data and address busses. The interior is no less tidy, with the 6502 microprocessor — date code from 1995 — and associated support chips neatly arranged on perf board. The construction method is wire wrapping, in keeping with the old-school look and feel. Even the hand-drawn schematic is a work of art — shades of [Forrest Mims].

As for programming, this machine is as low-level as it gets. Nothing but 6502 machine language here, entered manually with the toggle switches, or via an externally programmed ROM. The machine can only address 1k of memory, a limit which the code to support the RPN calculator add-on [Yamada] also built brushes up against, at 992 bytes. The calculator keypad has a 20-key matrix pad and an eight-digit dot-matrix LED display, and can do the four basic operations on fixed-point binary-coded decimal inputs. The brief video below shows the calculator in action.

We love the look of this build and we’re eager to see more like it. We’ve seen a ton of 6502 builds from discrete chips lately, and while we love those too, it’s nice to see one of the big old DIPs put back in action for a change.

Continue reading “Another Kind Of “Bare Metal”: 6502 Computer Powers RPN Calculator”