We like scale models here, but how small can you shrink the very large? If you’re [Frans], it’s pretty small indeed: his Micro Tellurium fits the orbit of the Earth on top of an ordinary pencil. While you’ll often see models of Earth, Moon and Sun’s orbital relationship called “Orrery”, that’s word should technically be reserved for models of the solar system, inclusive of at least the classical planets, like [Frans]’s Gentleman’s Orrery that recently graced these pages. When it’s just the Earth, Moon and Sun, it’s a Tellurium.

The whole thing is made out of brass, save for the ball-bearings for the Earth and Moon. Construction was done by a combination of manual milling and CNC machining, as you can see in the video below. It is a very elegant device, and almost functional: the Earth-Moon system rotates, simulating the orbit of the moon when you turn the ring to make the Earth orbit the sun. This is accomplished by carefully-constructed rods and a rubber O-ring.

Unfortunately, it seems [Franz] had to switch to a thicker axle than originally planned, so the tiny moon does not orbit Earth at the correct speed compared to the solar orbit: it’s about half what it ought to be. That’s unfortunate, but perhaps that’s the cost one pays when chasing smallness. It might be possible to fix in a future iteration, but right now [Franz] is happy with how the project turned out, and we can’t blame him; it’s a beautiful piece of machining.

It should be noted that there is likely no tellurium in this tellurium — the metal and the model share the same root, but are otherwise unrelated. We have featured hacks with that element, though.

Thanks to [Franz] for submitting this hack. Don’t forget: the tips line is always open, and we’re more than happy to hear you toot your own horn, or sing the praises of someone else’s work. Continue reading “Tiny Tellurium Orbits Atop A Pencil”

Peek behind the polished face and you’ll find a mechanical sleight of hand. This isn’t your grandfather’s gear-laden

Peek behind the polished face and you’ll find a mechanical sleight of hand. This isn’t your grandfather’s gear-laden

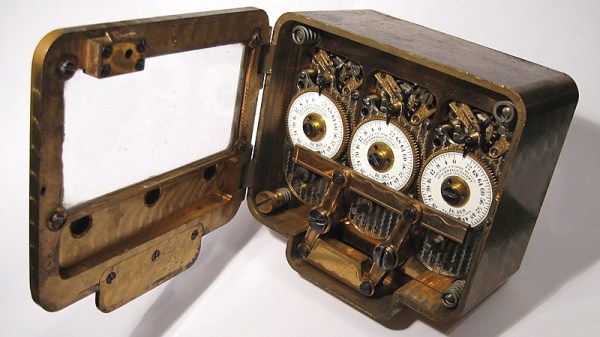

The concept of a time lock is an old one, and here you can see an example of

The concept of a time lock is an old one, and here you can see an example of