Coming straight to you from the “Department of Redundant Redundancies” comes this clever hack that turns a Switch into a switch. More specifically, a network switch. Not even a half bad one either, judging by the speed tests [Cynthia Revström] performed after setting it all up. We wouldn’t advise you dump your existing network gear in favor of a repurposed game system, but perhaps in a pinch…

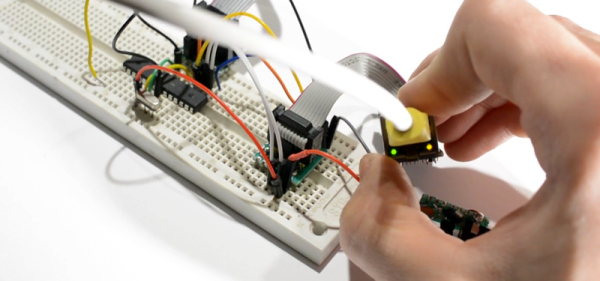

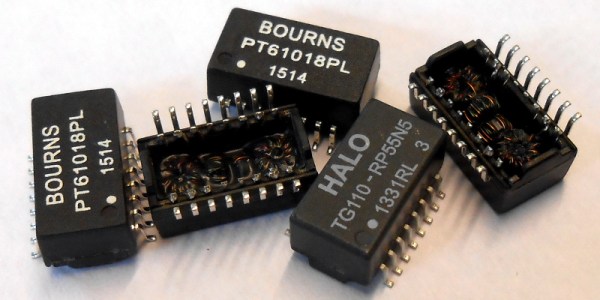

Despite what you might be thinking, there’s no hardware modifications at work here. This is a fully functional Nintendo Switch that’s just had two USB to Ethernet adapters plugged into it. The secret ingredient is the addition of some Penguin Power, up and running on Nintendo’s latest and greatest thanks to a project called switchroot.

With Linux running on the system, all [Cynthia] had to do was make sure that the USB to Ethernet adapters were supported, and fiddle around with the

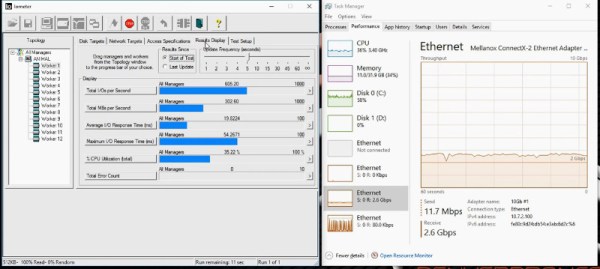

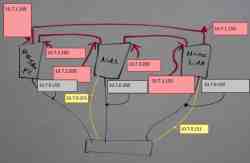

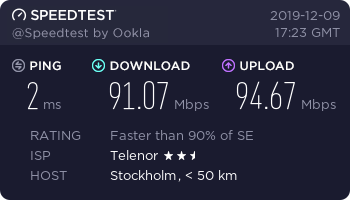

With Linux running on the system, all [Cynthia] had to do was make sure that the USB to Ethernet adapters were supported, and fiddle around with the brctl and ip commands to configure a bridge between the interfaces to get the packets moving. Putting the Switch between the main network and a test computer showed it had a throughput of just over 90 Mbps, which is about all that could be expected from the USB-connected network interfaces.

From here it wouldn’t have taken much more effort to get the system working as a wireless router and providing services like DHCP and NAT to clients. But since Nintendo didn’t see fit to call it the Router, that would’ve offered minimal meme value. There’s always next generation.

Seeing the Nintendo Switch do a surprisingly good job running as an Ethernet switch is even more surprising given the fact that it struggles to function with accessories that are actually intended for it. Though to be fair, the migration to USB-C has been a little rockier than most of us would have hoped.