For a full-fledged, bells-and-whistles driving simulator a number of unique human interface devices are needed, from pedals and shifters to the steering wheel. These steering wheels often have force feedback, with a small motor inside that can provide resistance to a user’s input that feels the same way that a steering wheel on a real car would. Inexpensive or small joysticks often omit this feature, but [Jason] has figured out a way to bring this to even the smallest game controllers.

The mechanism at the center of his controller is a DC motor out of an inkjet printer. Inkjet printers have a lot of these motors paired with rotary encoders for precision control, which is exactly what is needed here. A rotary encoder can determine the precise position of the controller’s wheel, and the motor can provide an appropriate resistive force depending on what is going on in the game. The motors out of a printer aren’t plug-and-play, though. They also need an H-bridge so they can get driven in either direction, and the entire mechanism is connected to an Arduino in the base of the controller to easily communicate with a computer over USB.

In testing the controller does behave like its larger, more expensive cousins, providing feedback to the driver and showing that it’s ready for one’s racing game of choice. It’s an excellent project for those who are space-constrained or who like to game on the go, but if you have more space available you might also want to check out [Jason]’s larger version built from a power drill instead parts from an inkjet.

Continue reading “Handheld Steering Wheel Controller Gets Force-Feedback”

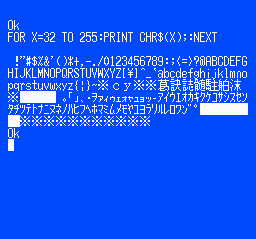

removable cartridge, complete with a BASIC interpreter and a collection of graphical editor tools for game creation.

removable cartridge, complete with a BASIC interpreter and a collection of graphical editor tools for game creation. even a map editor. We think inputting BASIC code via a gamepad would get old fast, but it would work a little better for graphical editing.

even a map editor. We think inputting BASIC code via a gamepad would get old fast, but it would work a little better for graphical editing.