GPS is an incredibly powerful tool that allows devices such as your smartphone to know roughly where they are with an accuracy of around a meter in some cases. However, this is largely too inaccurate for many use cases and that accuracy drops considerably when inside such as warehouse robots that rely on barcodes on the floor. In response, researchers [Linguang Zhang, Adam Finkelstein, Szymon Rusinkiewicz] at Princeton have developed a system they refer to as MicroGPS that uses pictures of the ground to determine its location with sub-centimeter accuracy.

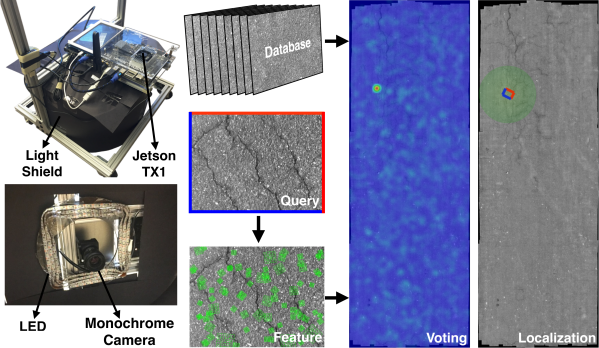

The system has a downward-facing monochrome camera with a light shield to control for exposure. Camera output feeds into an Nvidia Jetson TX1 platform for processing. The idea is actually quite similar to that of an optical mouse as they are often little more than a downward-facing low-resolution camera with some clever processing. Rather than trying to capture relative position like a mouse, the researchers are trying to capture absolute position. Imagine picking up your mouse, dropping it on a different spot on your mousepad, and having the cursor snap to a different part of the screen. To our eyes that are quite far away from the surface, asphalt, tarmac, concrete, and carpet look quite uniform. But to a macro camera, there are cracks, fibers, and imperfections that are distinct and recognizable.

They sample the surface ahead of time, creating a globally consistent map of all the images stitched together. Then while moving around, they extract features and implement a voting method to filter out numerous false positives. The system is robust enough to work even a month after the initial dataset was created on an outside road. They put leaves on the ground to try and fool the system but saw remarkably stable navigation.

Their paper, code, and dataset are all available online. We’re looking forward to fusion systems where it can combine GPS, Wifi triangulation, and MicroGPS to provide a robust and accurate position.

Video after the break.