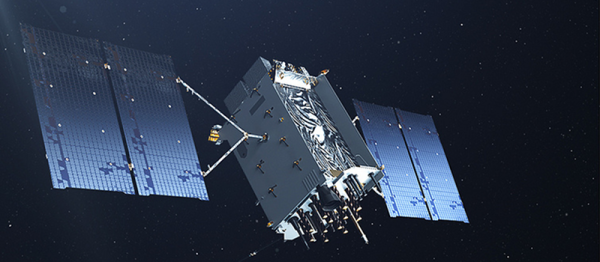

There’s a bug about to hit older GPS hardware that has echos of Y2K. Those old enough to have experienced the transition from the 1990s to the 2000s will no doubt recall the dreaded “Year 2000 Bug” that was supposed to spell the doom of civilization. Thanks to short-sighted software engineering that only recorded two digits for year, we were told that date calculations would fail en masse in software that ran everything from the power grid to digital watches. Massive remediation efforts were undertaken, companies rehired programmers whose outdated skills were suddenly back in demand, and in the end, pretty much nothing actually happened.

Yet another epoch is upon us, far less well-known but potentially deeper and more insidious. On Saturday April 6, 2019 — that’s tomorrow — GPS receivers may suffer from software issues due to rollover of their time counters. This could result in anything from minor inconvenience to major confusion, with an outside chance of chaos. Some alarmists are even stating that they won’t fly this weekend, for fear of the consequences.

So what are the real potential consequences, and what’s the problem with GPS in the first place? Unsurprisingly, it all boils down to basic math.