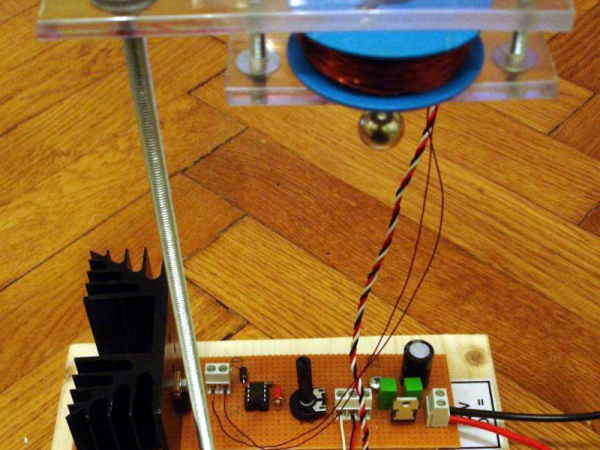

Recently, [Solder Hub] put together a brief video that demonstrates the basics of a Hall Effect sensor — in this case, one salvaged from an old CPU fan. Two LEDs, a 100 ohm resistor, and a 3.7 volt battery are soldered onto a four pin Hall effect sensor which can toggle one of two lights in response to the polarity of a nearby magnet.

If you’re interested in the physics, the once sentence version goes something like this: the Hall Effect is the production of a potential difference, across an electrical conductor, that is transverse to an electric current in the conductor and to an applied magnetic field perpendicular to the current. Get your head around that!

Of course we’ve covered the Hall effect here on Hackaday before, indeed, our search returned more than 1,000 results! You can stick your toe in with posts such as A Simple 6DOF Hall Effect ‘Space’ Mouse and Tracing In 2D And 3D With Hall Effect Sensors.