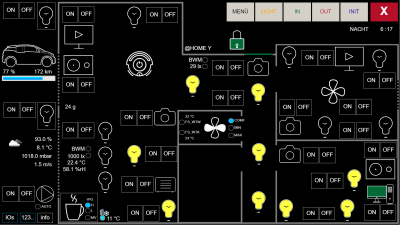

If you’re lucky enough to have central heating and/or air conditioning, with an automatic thermostat, you probably don’t have to worry too much about the outside temperature. But central HVAC is far from the only way of maintaining temperature in a home. From wood stoves to boilers there are many options depending on your climate and home type, and [Murphy’s Law] has a decentralized baseboard system instead of something centralized. An ESP8266 solution was found that was able to tie them all together.

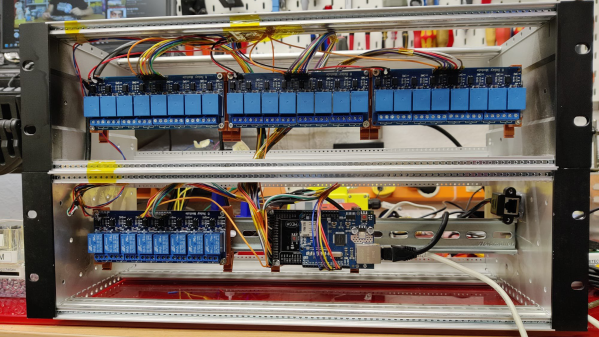

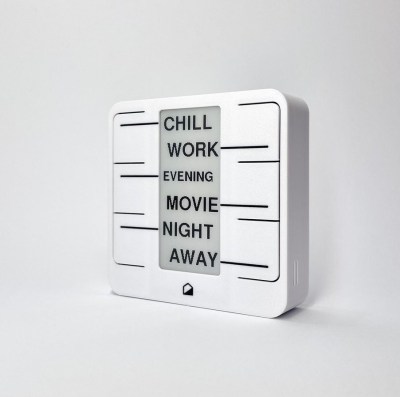

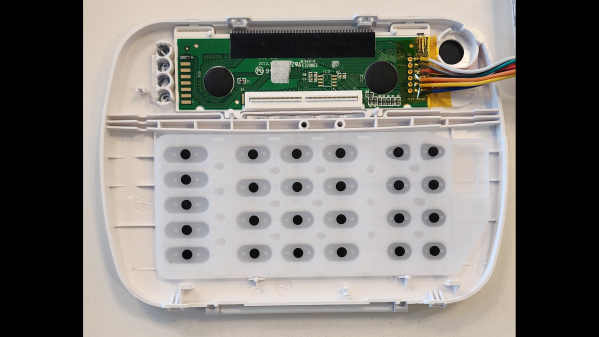

There are other types of baseboard heaters, but in [Murphy’s Law]’s case the heaters were electric with a separate thermostat for each heater. Rather than build a control system from the ground up to replace the thermostats, turnkey smart wall switches were used instead. These switches happened to be based on the popular ESP8266 microcontroller, like plenty of other off-the-shelf automation solutions, which meant less work needed to be done on the line voltage side and the microcontroller’s firmware could be easily customized for use with Home Assistant.

While [Murphy’s Law] doesn’t live in the home with the fleet of electric baseboard heaters anymore, the new home has a single baseboard heater to keep a bathroom warm since the central heating system doesn’t quite keep it warm enough. This system is able to scale up or down based on number of heaters, though, so it’s still a capable solution for the single room and has since been updated to use the ESP32. All of the code for this project is available on GitHub as well, and for those of you attempting to add other HVAC components to a home automation system this project that loops in a heat pump is worth taking a look at as well.