It looks like the third decade of the 21st century is off to a bit of a weird start, at least in the middle of the United States. There, for the past several weeks, mysterious squads of multicopters have taken to the night sky for reasons unknown. Witnesses on the ground report seeing both solo aircraft and packs of them, mostly just hovering in the night sky. In mid-December when the nightly airshow started, the drones seemed to be moving in a grid-search pattern, but that seems to have changed since then. These are not racing drones, nor are they DJI Mavics; witnesses report them to be 6′ (2 meters) in diameter and capable of staying aloft for 90 minutes. These are serious professional machines, not kiddies on a lark. So far, none of the usual government entities have taken responsibility for the flights, so speculation is all anyone has as to their nature. We’d like to imagine someone from our community will get out there with radio direction finding gear to locate the operators and get some answers.

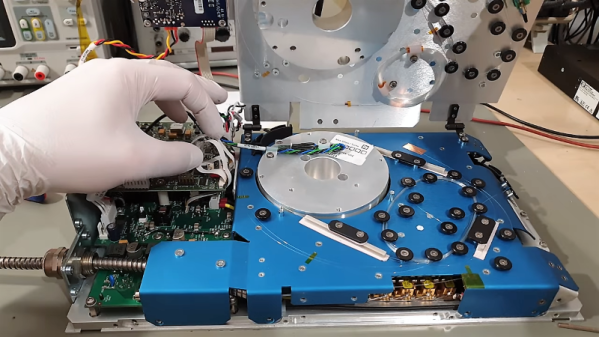

We all know that water and electricity don’t mix terribly well, but thanks to the seminal work of White, Pinkman et al (2009), we also know that magnets and hard drives are a bad combination. But that didn’t stop Luigo Rizzo from using a magnet to recover data from a hard drive. He reports that the SATA drive had been in continuous use for more than 11 years when it failed to recover after a power outage. The spindle would turn but the heads wouldn’t move, despite several rounds of percussive maintenance. Reasoning that the moving coil head mechanism might need a magnetic jump-start, he probed the hard drive case with a magnetic parts holder until the head started moving again. He was then able to recover the data and retire the drive. Seems like a great tip to file away for a bad day.

It seems like we’re getting closer to a Star Trek future every day. No, we probably won’t get warp drives or transporters anytime soon, and if we’re lucky velour tunics and Spandex unitards won’t be making a fashion statement either. But we may get something like Dr. McCoy’s medical scanner thanks to work out of MIT using lasers to conduct a non-contact medical ultrasound study. Ultrasound exams usually require a transducer to send sound waves into the body and pick up the echoes from different structures, with the sound coupled to the body through an impedance-matching gel. The non-contact method uses pulsed IR lasers to penetrate the skin and interact with blood vessels. The pulses rapidly heat and expand the blood vessels, effectively turning them into ultrasonic transducers. The sound waves bounce off of other structures and head back to the surface, where they cause vibrations that can be detected by a second laser that’s essentially a sophisticated motion sensor. There’s still plenty of work to do to refine the technique, but it’s an exciting development in medical imaging.

And finally, it may actually be that the future is less Star Trek more WALL-E in the unlikely event that Segway’s new S-Pod personal vehicle becomes popular. The two-wheel self-balancing personal mobility device is somewhat like a sitting Segway, except that instead of leaning to steer it, the operator uses a joystick. Said to be inspired by the decidedly not Tyrannosaurus rex-proof “Gyrosphere” from Jurassic World, the vehicle tops out at 24 miles per hour (39 km/h). We’re not sure what potential market for these things would need performance like that – it seems a bit fast for the getting around the supermarket and a bit slow for keeping up with city traffic. So it’s a little puzzling, although it’s clearly easier to fully automate than a stand-up Segway.