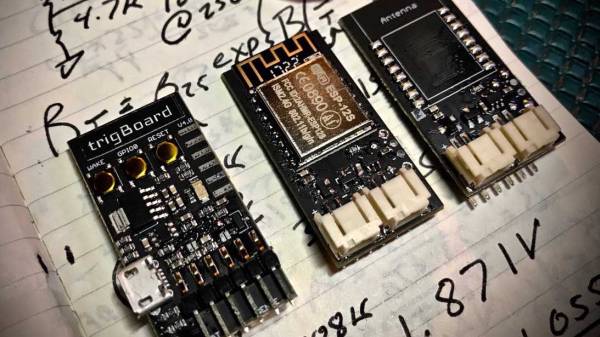

Given the popularity of hacking and repurposing Amazon Dash buttons, there appears to be a real need amongst tinkerers for a simple “do something interesting on the internet when a button is pressed” device. If you have this need but don’t feel like fighting to bend a Dash device to your will, take a look at [Kevin Darrah]’s trigBoard instead.

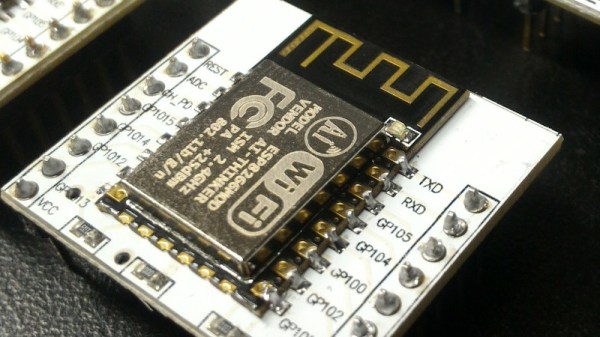

The trigBoard is a battery-powered, ESP8266-based board that includes some clever circuitry to help it barely sip power (less than one microamp!) while waiting to be triggered by a digital input. This input could be a magnetic reed switch, push button, or similar, and you can configure the board for either normally open or normally closed switches.

The clever hardware bits that allow for such low power consumption are explained in [Kevin]’s YouTube video, which we’ve also embedded after the break. To summarize: the EPS8266 spends most of it’s time completely unpowered. A Texas Instruments TPL5111 power timer chip burns 35 nanoamps and wakes the ESP8266 up every hour to check on the battery. This chip also has a manual wake pin, and it’s this pin – along with more power-saving circuitry – that’s used to trigger actions based on the external input.

Apparently the microcontroller can somehow distinguish between being woken up for a battery check versus a button press, so you needn’t worry about accidentally sending yourself an alert every hour. The default firmware is set up to use Pushbullet to send notifications, but of course you could do anything an EPS8266 is capable of. The code is available on the project’s wiki page.

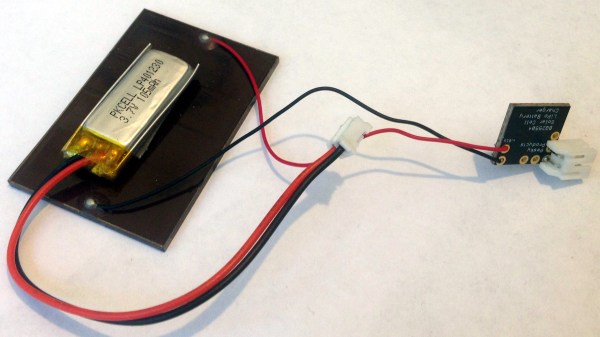

The board also includes a standard micro-JST connector for a LiPo battery, and can charge said battery through a micro-USB port. The trigBoard’s full schematic is on the wiki, and pre-built devices are available on Tindie.

[Kevin]’s hardware walkthrough video is embedded after the break.

Continue reading “Low-energy ESP8266-based Board Sleeps Like A Log Until Triggered” →