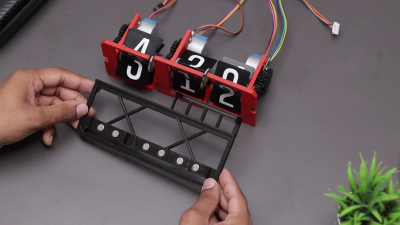

Magnets are pretty nice little tools. [EmGi] has used them in many a cool 3D printed build with great success. But getting them where you want can be really tricky. More often than not, you end up with glue all over your fingers, or the magnets fly out of place, or they stick together when you don’t want them to.

Well, [EmGi] created a mighty fine magnet insertion tool that you can print for yourself. It’s finger-operated and uses a single embedded magnet to place magnets wherever they’re needed.

Well, [EmGi] created a mighty fine magnet insertion tool that you can print for yourself. It’s finger-operated and uses a single embedded magnet to place magnets wherever they’re needed.

This thing went through several designs before [EmGi] ever printed it out. Originally, there were two magnets, but there was an issue where if the tool wasn’t lifted off perfectly, it would send the magnet flying.

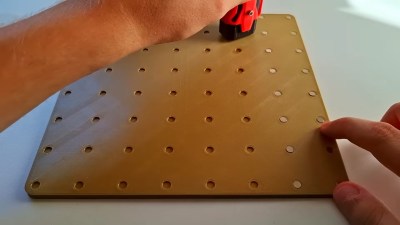

But now it works great, and [EmGi] even deposited an array of 64 magnets without using glue to test it out before printing a second one to handle the other polarity. Check out the build/demo video after the break.

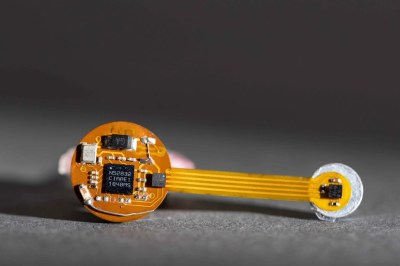

While you’re printing and placing magnets, why not make yourself a couple of magnetic switches? You can even make ’em for keyboards.