There was a time when the idea of an international space station would have been seen as little more than fantasy. After all, the human spaceflight programs of the United States and the Soviet Union were started largely as a Cold War race to see which country would be the first to weaponize low Earth orbit and secure what military strategists believed would be the ultimate high ground. Those early rockets, not so far removed from intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), were fueled as much by competition as they were kerosene and liquid oxygen.

Luckily, cooler heads prevailed. The Soviet Almaz space stations might have carried a 23 mm cannon adapted from tail-gun of the Tu-22 bomber to ward off any American vehicles that got too close, but the weapon was never fired in anger. Eventually, the two countries even saw the advantage of working together. In 1975, a joint mission saw the final Apollo capsule dock with a Soyuz by way of a special adapter designed to make up for the dissimilar docking hardware used on the two spacecraft.

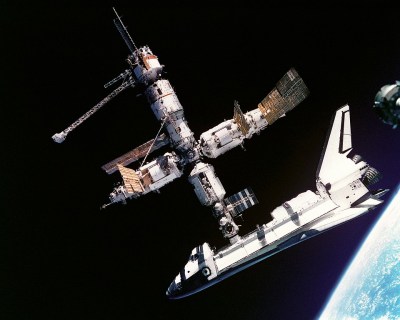

Relations further improved following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, with America’s Space Shuttle making nine trips to the Russian Mir space station between 1995 and 1997. A new era of cooperation had begun between the world’s preeminent space-fairing countries, and with the engineering lessons learned during the Shuttle-Mir program, engineers from both space agencies began laying the groundwork for what would eventually become the International Space Station.

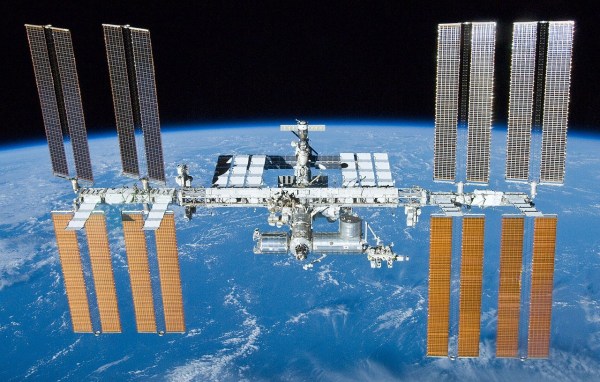

Unfortunately after more than twenty years of continuous US and Russian occupation of the ISS, it seems like the cracks are finally starting to form in this tentative scientific alliance. With accusations flying over who should take the blame for a series of serious mishaps aboard the orbiting laboratory, the outlook for future international collaboration in Earth orbit and beyond hasn’t been this poor since the height of the Cold War.

Continue reading “As ISS Enters Its Final Years, Politics Take Center Stage”