[Matt] created an animated gif of New Horizon’s Pluto flyby. The source images were taken from the the raw LORRI images, modified so the background star field could be seen, and assembled with OpenCV. Because Pluto and Charon orbit each other around a point above Pluto’s surface, simply putting Pluto in the center of each frame wouldn’t work. It’s the best visual explanation of this weird arrangement yet, all brought to you by the magic of OpenCV and Python.

On the subject of Kickstarter creators that don’t understand the conservation of energy, I present this.

We don’t know exactly what’s going on with this one, but here’s a swimming pool covered with RGB LEDs. It’s controlled by two Rainbowduinos, and looks like the coolest disco floor you’ve ever seen.

[Frank]’s 2011 Hundai Santa Fe wasn’t cool enough, so he added an F16 flight stick to his shift knob. The choice of joystick is paramount here: Saitek joysticks look too techy, Logitech ones are too expensive, and the Warthog H.O.T.A.S costs $400. Joysticks are extremely niche peripherals these days, it seems. He ended up strapping an old F16 joystick from the 90s on his shift knob, and it looks close enough to the real thing.

Two bodgers are stuffing the engine from a Toyota Celica into a 1980 Mini, and they’re trying to make it look stock. We’ve seen their project before, and now there’s a new episode. In this episode: the pedal box, the steering wheel, and figuring out how to make the car drive straight.

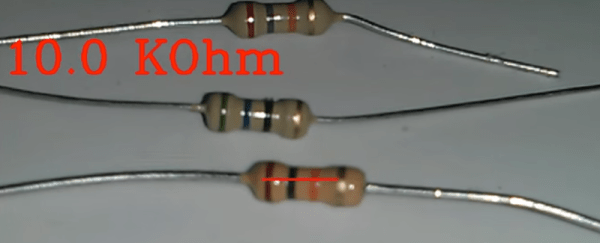

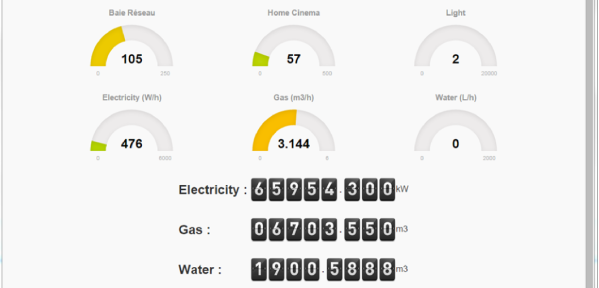

So he figured out a way to extract data from the existing meters. For the Electricity meter, he thought of using current clamps, but punted that idea considering them to be suited more for instantaneous readings and prone for significant drift when measuring cumulative consumption. Eventually, he hit upon a pretty neat hack. He took a slot type opto coupler, cut it in half, and used it as a retro-reflective sensor that detected the black band on the spinning disk of the old electro-mechanical meter. Each turn of the disk corresponds to 4 Watt-hours. A little computation, and he’s able to deduce Watt-hours and Amps used. The sensor is hooked up to an Arduino Pro-mini which then sends the data via a nRF24L01+ module to the main circuit located inside his house. The electronics are housed in a small enclosure, and the opto-sensor looks just taped to the meter. He has a nice tip on aligning the infra-red opto-sensor – use a camera to check it (a phone camera can work well).

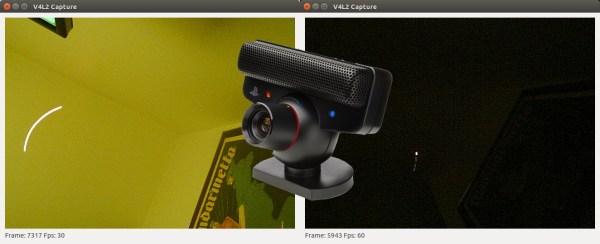

So he figured out a way to extract data from the existing meters. For the Electricity meter, he thought of using current clamps, but punted that idea considering them to be suited more for instantaneous readings and prone for significant drift when measuring cumulative consumption. Eventually, he hit upon a pretty neat hack. He took a slot type opto coupler, cut it in half, and used it as a retro-reflective sensor that detected the black band on the spinning disk of the old electro-mechanical meter. Each turn of the disk corresponds to 4 Watt-hours. A little computation, and he’s able to deduce Watt-hours and Amps used. The sensor is hooked up to an Arduino Pro-mini which then sends the data via a nRF24L01+ module to the main circuit located inside his house. The electronics are housed in a small enclosure, and the opto-sensor looks just taped to the meter. He has a nice tip on aligning the infra-red opto-sensor – use a camera to check it (a phone camera can work well).