If you’ve ever tried to take a picture of a fast moving object, you know how important timing is. You might only have one chance, and if you hit the shutter a bit too early or too late, the shot could be ruined. Past a certain point, no human camera operator can react quickly enough. Which is exactly why [Krzysztof Krześlak] created PiXPi.

In the past we’ve seen high-speed flashes designed to “freeze time” by illuminating the scene at the precise moment, and while PiXPi can technically do that, it also offers a few alternate methods of capturing that perfect moment. The idea here is to give the photographer the best chance of getting the shot they’re after by offering them as many tools as possible.

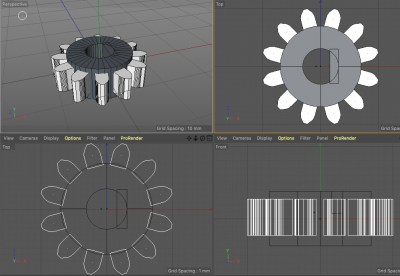

Essentially, PiXPi is a microcontroller that allows you to orchestrate your DSLR’s trigger, external flashes, and various other sensors and devices using an easy to use graphical programming interface from your smartphone. So for example, you could program the PiXPi to trigger your camera when it detected a loud enough noise.

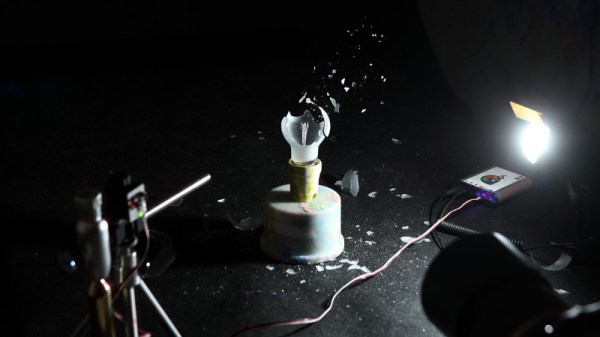

Essentially, PiXPi is a microcontroller that allows you to orchestrate your DSLR’s trigger, external flashes, and various other sensors and devices using an easy to use graphical programming interface from your smartphone. So for example, you could program the PiXPi to trigger your camera when it detected a loud enough noise.

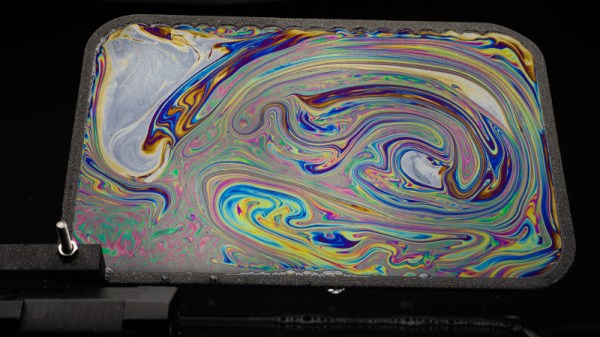

But the device also allows you to be a bit more proactive. Rather than sitting back and waiting for a signal to fire off the camera, the PiXPi can directly take control of the action. As an example, [Krzysztof] has created an electronically triggered valve which can release a drop of liquid on command. Using PiXPi, the photographer can quickly put together a routine that triggers a drop, waits the few milliseconds it takes for it to hit the target, and then snaps a picture.

The goal of the 2019 Hackaday Prize is to develop a product fit for production, and naturally a huge part of that is having a well thought-out design. But if you’re ultimately looking to sell said product, it’s also very important to keep the needs of the end user in mind. To that end, we think [Krzysztof] has done a great job by not only making the system very flexible, but keeping it easy to use.