Twitch Plays Pokemon burst onto the then nascent livestreaming scene back in 2014, letting Twitch viewers take command of a Game Boy emulator running Pokemon Red via simple chat commands. Since then, the same concept has been applied to everything under the sun. Other video games, installing Linux, and even trading on the New York Stock Exchange have all been gameified through Twitch chat.

You, thirsty reader, are wondering how you can get a slice of this delicious action. Fear not, for with a bit of ramshackle code, you can let Twitch chat take over pretty much anything in, on, or around your computer.

It’s Just IRC

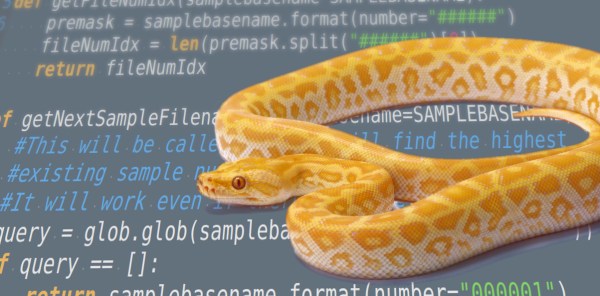

The great thing about Twitch chat is that it runs on vanilla IRC (Internet Relay Chat). The protocol has been around forever, and libraries exist to make interfacing easy. Just like the original streamer behind Twitch Plays Pokemon, we’re going to use Python because it’s great for fun little experiments like these. With that said, any language will do fine — just apply the same techniques in the relevant syntax.

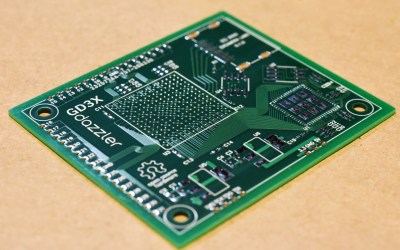

SimpleTwitchCommander, as I’ve named it on Github, assumes some familiarity with basic Python programming. The code will allow you to take commands from chat in two ways. Commands from chat can be tabulated, and only the one with the most votes executed, or every single command can be acted on directly. Actually getting this code to control your robot, video game, or pet viper is up to you. What we’re doing here is interfacing with Twitch chat and pulling out commands so you can make it do whatever you like. With that said, for this example, we’ve set up the code to parse commands for a simple wheeled robot. Let’s dive in.

Continue reading “Code Your Own Twitch Chat Controls For Robots — Or Just About Anything Else!”