[Patrick McDavid] and his wife had a legitimate work-related reason for writing some Python code that would pull the exact latitude and longitude of the individual locations within a national retain chain from Google’s Geocoding API. But don’t worry about that part of the story. What’s important now is that this simple concept was then expanded into a pocket-sized device that will lead the holder to the nearest White Castle or Five Guys location.

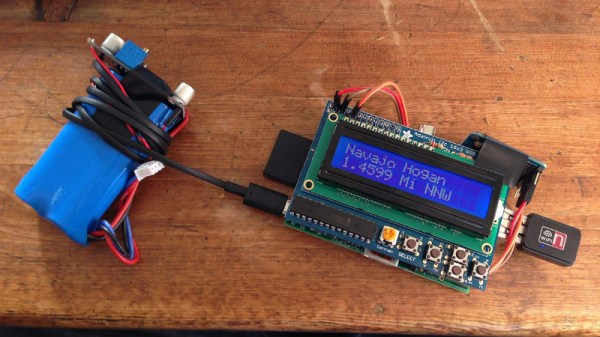

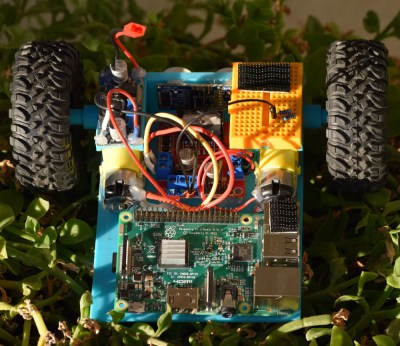

The device, which [Patrick] lovingly referrers to as the “Cheeseburger Compass”, uses a Raspberry Pi 3, an Adafruit 16×2 LCD with keypad, a GPS module, and the requisite battery and charger circuit to make it mobile. With the coordinates for the various places one can obtain glorious artery clogging meat circles loaded up, the device will give the user the cardinal direction and current distance from the nearest location of the currently selected chain.

The device, which [Patrick] lovingly referrers to as the “Cheeseburger Compass”, uses a Raspberry Pi 3, an Adafruit 16×2 LCD with keypad, a GPS module, and the requisite battery and charger circuit to make it mobile. With the coordinates for the various places one can obtain glorious artery clogging meat circles loaded up, the device will give the user the cardinal direction and current distance from the nearest location of the currently selected chain.

[Patrick] has published the source code for this meat-seeking gadget on GitHub, but notes that most of it is just piecing together existing libraries and tools. As with many Python projects, it turns out there’s already a popular library to do whatever it is you were trying to do manually, so his early attempts at calculating distances and bearings were ultimately replaced with turn-key solutions. Though he did come up with a quick piece of code that would convert a compass heading in degrees to a cardinal direction that he couldn’t find a better solution for. Maybe he should make it a library…

Sadly the original Cheeseburger Compass got destroyed from being carried around so much, but at least it died doing what it loved. [Patrick] says a second version of the device would likely switch over to a microcontroller rather than the full Raspberry Pi experience, as it would make the device much smaller and greatly improve on the roughly two hour battery life.

This project reminds us of the various geocache devices we’ve covered in the past, but with the notable addition of hot sizzling meat. Talk about improving on a good thing.