Before everyone had a cell phone alarm to wake them up in the mornings, most of us used clock radios that would faithfully sit by our beds for years. You could have either a blaring alarm to wake you up, or be gently roused from slumber by one of your local radio stations. These devices aren’t as commonly used anymore, so if you have one sitting in your parts drawer you can make some small changes and use it to receive radio stations from a little further away than you’d expect.

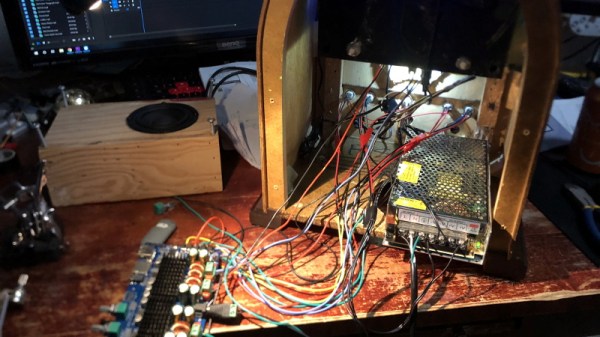

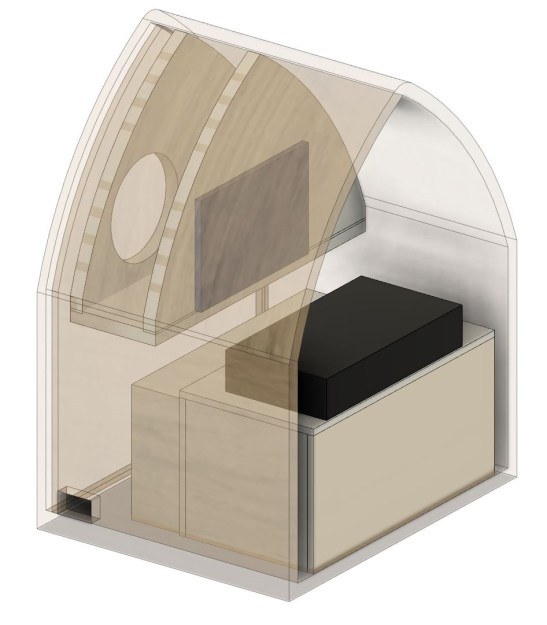

This Panasonic clock radio from [Ryan Flowers] has several upgrades compared to the old clock radio hardware. For one, it now can receive signals on the 7 and 14 MHz bands (40 and 20 meters). It does this by using separate bandpass filters for each frequency range, controlled by a QRP Labs VFO kit which can switch between the two filters automatically once programmed. The whole thing is powered by 8 AA batteries, true to form with a clock radio from the ’90s.

[Ryan] notes that his first iteration was a little quiet but he’s now able to receive radio stations from as far away from Japan with this receiver. Even without a license, you can make these changes and listen in to stations from all around the world, as long as you don’t start transmitting. If you want to make a small upgrade from this clock radio though, it’s not that hard to get into.