No one watches video anymore. Cable cutters are digging into Verizon’s profits, and YouTube is a shadow of its 2005 self. What are people consuming now? Animated gifs. This is the bread and butter of the meme economy. Personally, all my investments are sunk deep into Gandolf / Balrog gifs, with each character replaced with Trump and Hillary. I expect a tidy profit on November 9th.

With animated gifs being the de facto method of sharing moving pictures, the world will belong to those who can create them. Phones are fine, but strangely video cameras, DSLRs, and other high-end photography equipment are the norm. This is idiotic, of course, because high-definition images are just a fad, and audio is useless.

Finally, there’s an answer. [Nick Brewer] created a camera that only takes animated gifs. I cannot stress this enough: this animated gif cam is a serious contender for a technical Oscar. Kubrick wept.

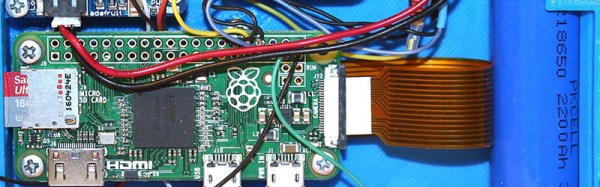

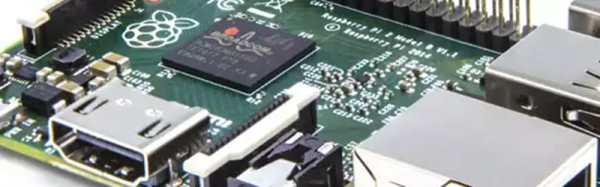

For the hardware, [Nick] went with a Raspberry Pi and Raspberry Pi camera. A combination of software ranging from PiCamera, GraphicsMagick, and GifCam turns this tiny bit of hardware into a machine dedicated to content creation in the hippest new medium. Other hardware includes a battery – either a normal LiPo ‘pouch’ cell, or an 18650 cell. Other hardware includes an Adafruit Powerboost 500 charge controller and a neat illuminated push button.

The 3D-printed enclosure is where this project really shines. Hearkening back to an older time, this camera includes a real viewfinder for all your gonzo giffing. The camera is charged through a completely normal USB port, and even the Pi’s SD card is accessible without disassembling the camera. There are even some paper wrappers for this camera to give it a 90s disposable camera aesthetic.

Of course, this isn’t the first camera dedicated to the creation of animated gifs. Before the C.H.I.P., Next Thing Co released OTTO, a camera designed for gifs. [Nick]’s project, though, is a camera dedicated completely to gifs. It is the greatest technical achievement of our time, for the creation of content in the greatest artistic medium.