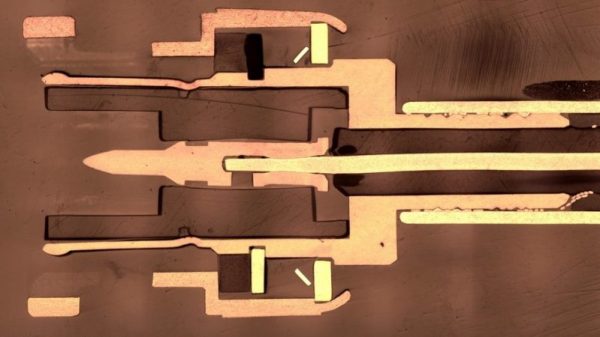

We’ve seen our share of 3D printed antennas before, but none as well documented and professionally tested as [Glenn]’s 3D printed and metalized horn antennas. It certainly helps that [Glenn] is the principal engineer at an antenna testing company, with access to an RF anechoic chamber and other test equipment.

Horn antennas are a fairly simple affair, structurally speaking, with a straight-sided horn-shaped “cone” and a receptacle for standardized waveguide or with an appropriate feed, coaxial adapters. They are moderately directional and can cover a wide range of frequencies. These horns are often used in radar guns and as feedhorns for parabolic dishes or other types of larger antenna. They are also used to discover the cosmic microwave background radiation of our universe and win Nobel Prizes.

[Glenn]’s antennas were modeled in Sketchup Make, and those files plus standard STL files are available for download. To create your own horn, print the appropriate file on a normal consumer-grade fused deposition printer. For antennas that perform well in WiFi frequency ranges you may need to use a large-format printer, as the prints can be “the size of a salad bowl”. Higher frequency horns can easily fit on most print beds.

After printing, [Glenn] settled on a process of solvent smoothing the prints, then metalizing them with commonly available conductive spray paints. The smoothing was found to be necessary to achieve the expected performance. Two different paints were tested, with a silver-based coating being the clear winner.

The full write-up has graphs of test results and more details on the process that led to these cheap, printed antenna that rival the performance of more expensive commercial products.

If you’re interested in other types of 3D printed antenna, we’ve previously covered a helical satcom feed, a large discone antenna, and an aluminum-taped smaller discone antenna.

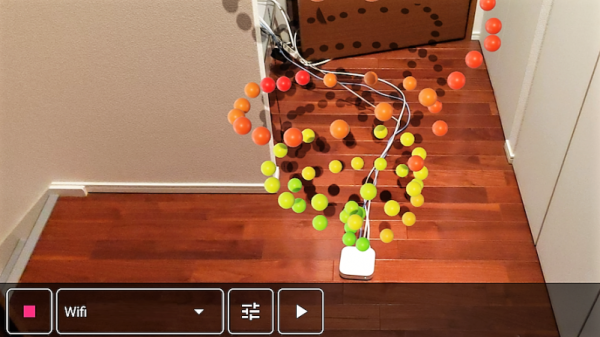

Unwilling to go full [Geordi La Forge] to be able to visualize RF, [Ken Kawamoto] built the next best thing –

Unwilling to go full [Geordi La Forge] to be able to visualize RF, [Ken Kawamoto] built the next best thing –