Humans weren’t the first organisms on this planet to figure out how to turn the abundance of nitrogen in the atmosphere into a chemically useful form; that honor goes to some microbes that learned how to make the most of the primordial soup they called home. But to our credit, once [Messrs. Haber and Bosch] figured out how to make ammonia from thin air, we really went gangbusters on it, to the tune of 8 million tons per year of the stuff.

While it’s not likely that [benchtop take on the Haber-Bosch process demonstrated by [Marb’s lab] will turn out more than the barest fraction of that, it’s still pretty cool to see the ammonia-making process executed in such an up close and personal way. The industrial version of Haber-Bosch uses heat, pressure, and catalysts to overcome the objections of diatomic nitrogen to splitting apart and forming NH3; [Marb]’s version does much the same, albeit at tamer pressures.

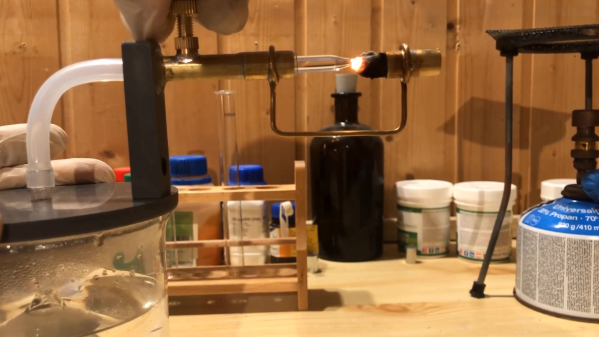

[Marb]’s process starts with hydrogen made by dripping sulfuric acid onto zinc strips and drying it through a bed of silica gel. The dried hydrogen then makes its way into a quartz glass reaction tube, which is heated by a modified camp stove. Directly above the flame is a ceramic boat filled with catalyst, which is a mixture of aluminum oxide and iron powder; does that sound like the recipe for thermite to anyone else?

A vial of Berthelot’s reagent, which [Marb] used in his recent blood ammonia assay, indicates when ammonia is produced. To start a run, [Marb] first purges the apparatus with nitrogen, to prevent any hydrogen-related catastrophes. After starting the hydrogen generator and flaring off the excess, he heats up the catalyst bed and starts pushing pure nitrogen through the chamber. In short order the Berthelot reagent starts turning dark blue, indicating the production of ammonia.

It’s a great demonstration of the process, but what we like about it is the fantastic tips about building lab apparatus on the cheap. Particularly the idea of using hardware store pipe clamps to secure glassware; the mold-it-yourself silicone stoppers were cool too.

Continue reading “Benchtop Haber-Bosch Makes Ammonia At Home”

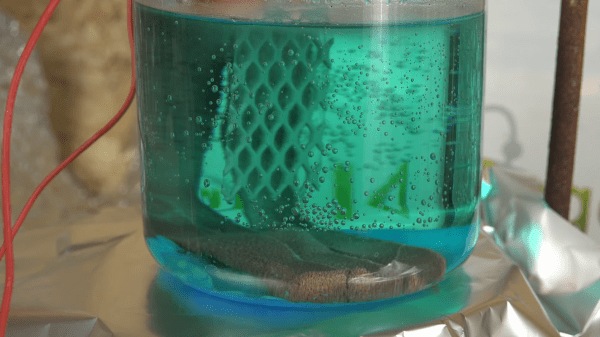

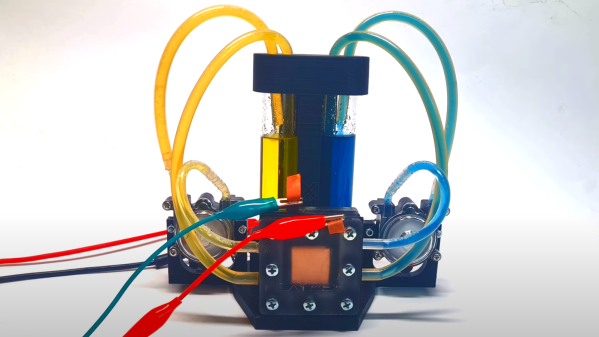

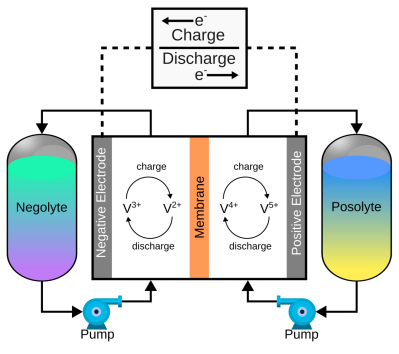

of a pair of electrolytes. These are held externally to the cell and connected with a pair of pumps. The capacity of a flow battery depends not upon the electrodes but instead the volume and concentration of the electrolyte, which means, for stationary installations, to increase storage, you need a bigger pair of tanks. There are even 4 MWh containerised flow batteries installed in various locations where the storage of renewable-derived energy needs a buffer to smooth out the power flow. The neat thing about vanadium flow batteries is centred around the versatility of vanadium itself. It can exist in four stable oxidation states so that a flow battery can utilise it for both sides of the reaction cell.

of a pair of electrolytes. These are held externally to the cell and connected with a pair of pumps. The capacity of a flow battery depends not upon the electrodes but instead the volume and concentration of the electrolyte, which means, for stationary installations, to increase storage, you need a bigger pair of tanks. There are even 4 MWh containerised flow batteries installed in various locations where the storage of renewable-derived energy needs a buffer to smooth out the power flow. The neat thing about vanadium flow batteries is centred around the versatility of vanadium itself. It can exist in four stable oxidation states so that a flow battery can utilise it for both sides of the reaction cell.