AIs can now apparently carry on a passable conversation, depending on what you classify as passable conversation. The quality of your local pub’s banter aside, an AI stuck in a text box doesn’t have much of a living quality. human. An AI that holds a conversation aloud, though, is another thing entirely. [William Franzin] has whipped up just that on amateur radio. (Video, embedded below.)

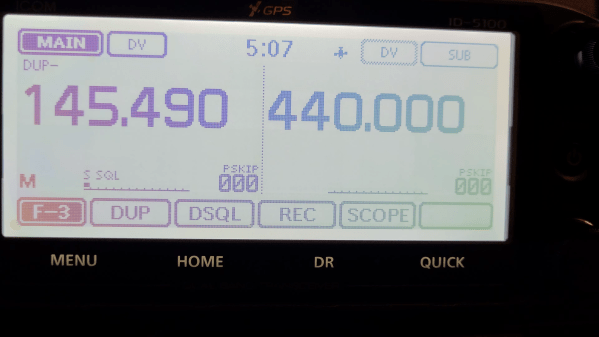

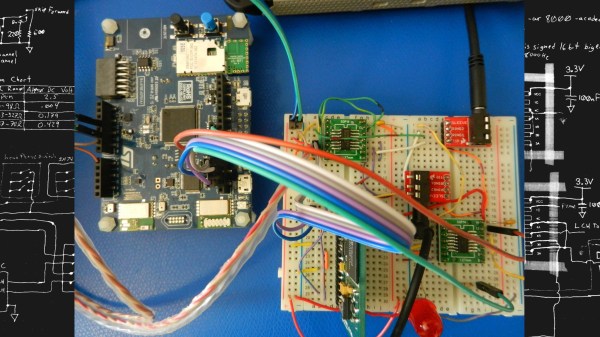

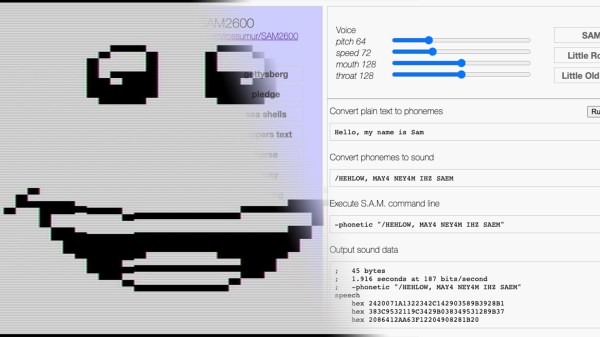

The concept is straightforward, if convoluted. A DSTAR digital voice transmission is received, which is then transcoded to regular digital audio. The audio then goes through a voice recognition engine, and that is used as a question for a ChatGPT AI. The AI’s output is then fed to a text-to-speech engine, and it speaks back with its own voice over the airwaves.

[William] demonstrates the system, keying up a transmitter to ask the AI how to get an amateur radio licence. He gets a pretty comprehensive reply in return.

The result is that radio amateurs can call in to ChatGPT with questions, and can receive actual spoken responses from the AI. We can imagine within the next month, AIs will be chatting it up all over the airwaves with similar setups. After all, a few robots could only add more diversity to the already rich and varied ham radio community. Video after the break.