We love to see projects revisited, especially when new materials or methods make it worth giving the first design another go around. This twin-turbine vacuum-powered Dremel tool is a perfect example of what better tools can do for a build.

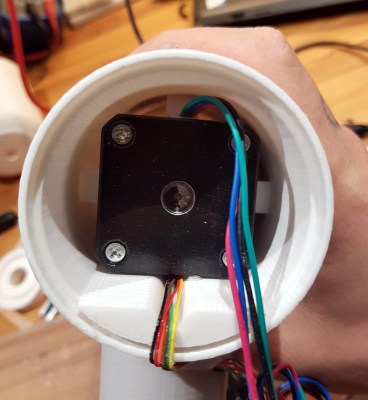

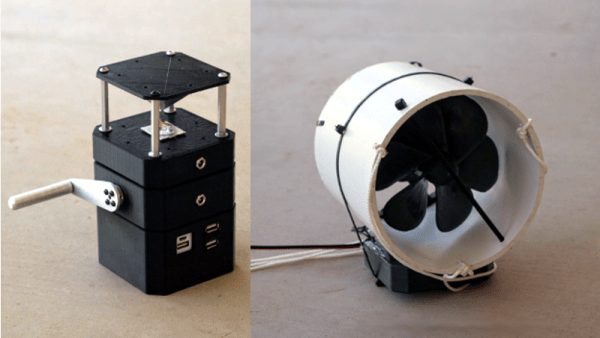

You may recall [JohnnyQ90]’s first attempt at a vacuum powered rotary tool. That incarnation, very similar in design to the current work, was entirely 3D-printed, and caused no little controversy in the comments about the wisdom of spinning anything made on an FDM printer at 43,000 RPM. Despite the naysaying, [Johnny] appears to have survived his own creation. But the turbo-tool did have its limitations, including somewhat anemic torque. This version, machined rather than printed and made almost completely from aluminum, seems to have solved that problem, perhaps thanks to the increased mass of the rotating parts. The twin rotors and the stator were milled with a 5-axis CNC machine, which has been a great addition to [JohnnyQ90]’s shop. The turbine shaft, looking like something from a miniature jet engine, was meticulously balanced using magnets mounted in the headstock and tailstock of a lathe. The video below shows the build and a few tests; we’re not big fans of the ergonomics of holding the tool on the end of that bulky hose, but it sure seems to work well. And that sound!

We first noticed [JohnnyQ90] when he machined aluminum from soda cans to make a mini Tesla turbine. His builds have come a long way since then, and we look forward to what he’ll come up with next.

Continue reading “Vacuum-Powered Rotary Tool Redux, This Time Machined”