You know those bottle fillers at schools and airports? What if you had one of those at home?

We know what you’re going to say: “My fridge has one of those!” Well ours doesn’t, and even though [Chris Courses’] fridge did, his bottle of choice didn’t fit in the vertically-challenged water and ice hutch, nor did it fill autonomously. The solution was to build a dubiously placed, but nonetheless awesome custom bottle filler in his kitchen.

The plumbing for the project couldn’t be more straight-forward: a 5-year undersink water filter, electronically actuated valve, some tubing, and a T to splice into the existing water line going to the fridge. Where the rubber hits the road is making this look nice. [Chris] spends a lot of time printing face plates, pouring resin as a diffuser, and post processing. After failing on one formulation of resin, the second achieves a nice look, and the unit is heavily sanded, filled, painted, prayed over, and given the green light for installation.

The plumbing for the project couldn’t be more straight-forward: a 5-year undersink water filter, electronically actuated valve, some tubing, and a T to splice into the existing water line going to the fridge. Where the rubber hits the road is making this look nice. [Chris] spends a lot of time printing face plates, pouring resin as a diffuser, and post processing. After failing on one formulation of resin, the second achieves a nice look, and the unit is heavily sanded, filled, painted, prayed over, and given the green light for installation.

For the electronics [Chris] went for a Raspberry Pi to monitor four buttons and dispense a precise allotment tailored to each of his favorite drinking vessels. While the dispenser is at work, three rows of LEDs play an animated pattern. Where we begin to scratch our heads is the demo below which shows there is no drain or drip tray below the dispenser — seems like an accident waiting to happen.

Our remaining questions are about automating the top-off process. At first blush you might wonder why a sensor wasn’t included to shut off the filler automatically. But how would that work? The dispenser needs to establish the height of the bottle and that’s a non-trivial task, perhaps best accomplished with computer vision or a CCD line sensor. How would you do it? Continue reading “Bottle Filler Perfectly Tops Your Cup”

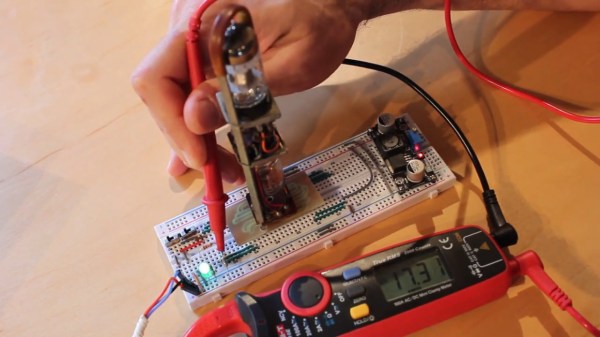

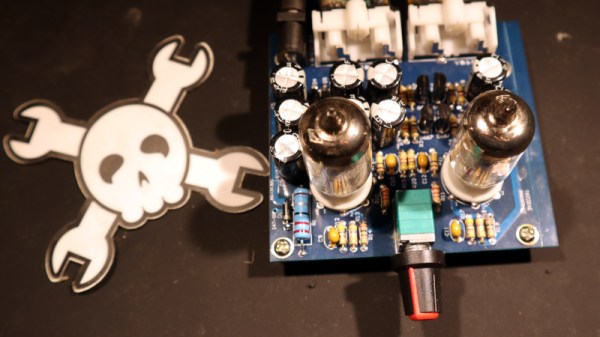

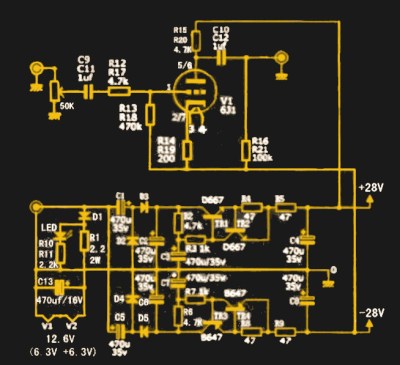

What I received for my tenner was a press-seal bag with a PCB and a pile of components, and not much else. No instructions, which would have been worrisome were the board not clearly marked with the value of each component. The circuit was on the vendor’s website and is so commonly used for these sort of kits that it can be found all over the web — a very conventional twin common-cathode amplifier using a pair of 6J1 miniature pentodes, and powered through a +25 V and -25 V supply derived from a 12 VAC input via a voltage multiplier and regulator circuit. It has a volume potentiometer, two sets of phono sockets for input and output, and the slightly naff addition of a blue LED beneath each tube socket to impart a blue glow. I think I’ll pass on that component.

What I received for my tenner was a press-seal bag with a PCB and a pile of components, and not much else. No instructions, which would have been worrisome were the board not clearly marked with the value of each component. The circuit was on the vendor’s website and is so commonly used for these sort of kits that it can be found all over the web — a very conventional twin common-cathode amplifier using a pair of 6J1 miniature pentodes, and powered through a +25 V and -25 V supply derived from a 12 VAC input via a voltage multiplier and regulator circuit. It has a volume potentiometer, two sets of phono sockets for input and output, and the slightly naff addition of a blue LED beneath each tube socket to impart a blue glow. I think I’ll pass on that component.