Thus far, the vast majority of human photographic output has been two-dimensional. 3D displays have come and gone in various forms over the years, but as technology progresses, we’re beginning to see more and more immersive display technologies. Of course, to use these displays requires content, and capturing that content in three dimensions requires special tools and techniques. Kim Pimmel came down to Hackaday Superconference to give us a talk on the current state of the art in advanced AR and VR camera technologies.

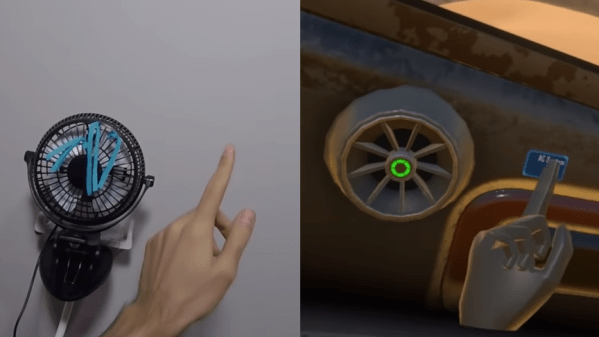

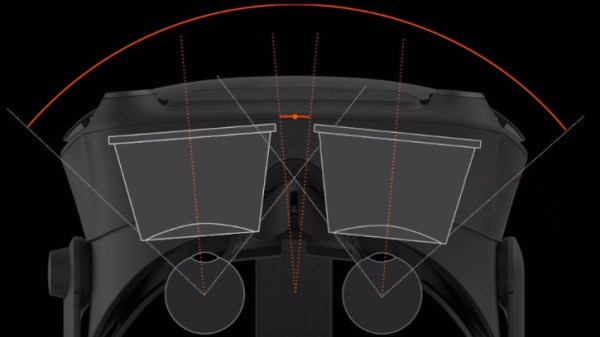

Through his work in the field of AR and VR displays, Kim became familiar with the combination of the Ricoh Theta S 360 degree camera and the Oculus Rift headset. This allowed users to essentially sit inside a photo sphere, and see the image around them in three dimensions. While this was compelling, [Kim] noted that a lot of 360 degree content has issues with framing. There’s no way to guide the observer towards the part of the image you want them to see.

Continue reading “Building Cameras For The Immersive Future”