Most hams can tell you that it’s possible to get a nasty RF burn if you accidentally touch an antenna while it’s transmitting. However, you can also cop a nasty surprise on the receiving end if you’re not careful, as explained in a video from [Grants Pass TV Repair].

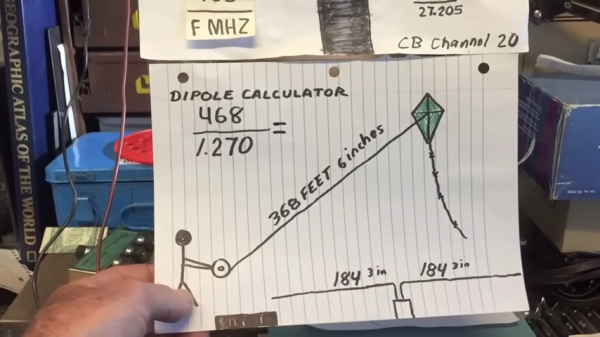

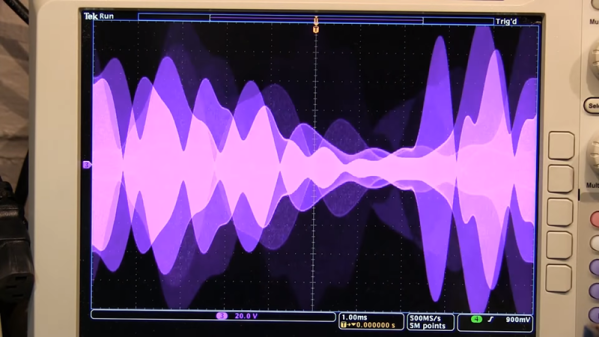

An experiment was used to demonstrate this fact involving a kite and a local AM broadcaster. A simple calculation revealed that an antenna 368 feet and 6 inches long would be resonant with the KAJO Radio signal at 1.270 MHz. At half the signal’s wavelength, an antenna that long would capture plenty of energy from the nearby broadcast antenna.

Enter the kite, which served as a skyhook to loft an antenna that long. With the wire in the air picking up a strong signal from the AM radio tower, it was possible to get a noticable RF burn simply by touching the end of the antenna.

The video explains that this is a risky experiment, but not only because of the risk of RF burn itself. It’s also easy to accidentally get a kite tangled in power lines, or to see it struck by lightning, both of which would create far greater injuries than the mild RF burn seen in the video. In any case, even if you know what you’re doing, you have to be careful when you’re going out of your way to do something dangerous in the first place.

AM radio towers aren’t to be messed with; they’ve got big power flowing. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Radio Frequency Burns, Flying A Kite, And You”