Last time, we covered storing and charging a 3000 Farad supercapacitor to build a solar-powered, portable spot welder. Since then, I’ve made some improvements to the charging circuit and gotten it running. To recap, the charger uses a DC-DC buck converter to convert a range of DC voltages down to 2.6 V. It can supply a maximum of 5 A though, and the supercapacitor will draw more than that if allowed to.

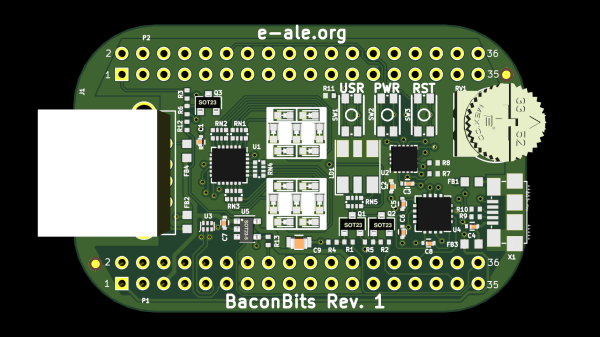

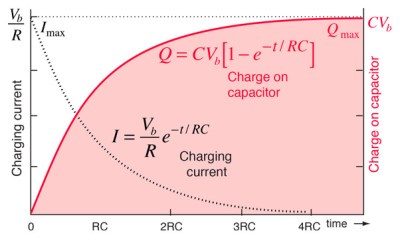

After some failed attempts, I had solved that by passing the buck converter output through a salvaged power MOSFET. A spare NodeMCU module provided pulse width modulated output that switched the MOSFET on for controlled periods of time to limit the charging current. That was fine, but a constant-voltage charger really isn’t the right way to load up a capacitor. Because the capacitor plates build up a voltage as it charges, the current output from a constant-voltage charger is high initially, but drops to a very low rate in the end.

Continue reading “Building A Portable Solar-Powered Spot Welder: Nearly Practical!”