Since the recent launch of the all-in-one Raspberry Pi 400, the global hardware community have taken to the new platform and are investigating its potential for hardware enhancements. On the back it has the same 40-pin expansion connector as its single-board siblings, but it’s horizontal rather than vertical, which means that all of the conventional HATs sit in a rather ungainly upright position.

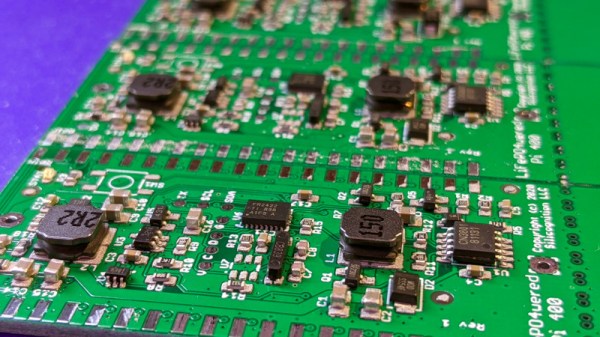

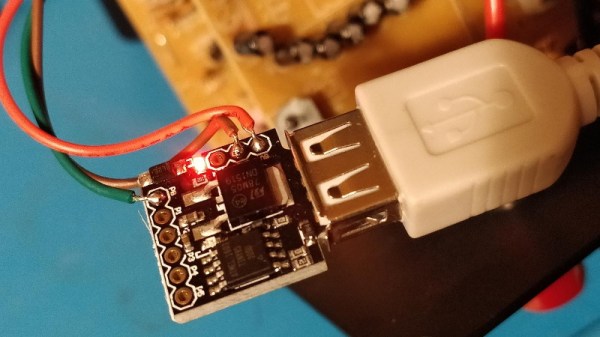

One of the first Pi 400 HATs we’ve seen comes from [Patrick Van Oosterwijck], who has made a very neat 18650-based UPS add-on that is intended to eventually fit in the back of the machine in a similar way to the home computer cartridge peripherals of old. Unfortunately not all has gone according to plan, and in finding out why that is the case we learn something about the design of the 400, and maybe even take a chance to reflect on the Pi Foundation itself.

On the face of it the 400’s interface is the same as that of its single board computer stablemates, but something this project reveals is that its 5 V pins have a current limit of 1 A. This turns out to preclude the type of plug-in Pi UPS that sits on a HAT that we’re used to, in that 1 A through the 5 V pin is no longer enough to run the computer.

This effectively puts a stop to [Patrick]’s project, though he can repurpose it for a Pi 4 and its siblings once he’s dealt with a converter chip overheating problem. He does however make a complaint about the Pi Foundation’s slowness in releasing such data about their products, and given that long-time Pi-watchers will remember a few other blips in the supply of Pi hardware data he has a point. A quick check of the Raspberry Pi GitHub repository reveals nothing related to the Pi 400 at the time of writing, and though it shares much with its Pi 4 sibling it’s obvious that there are enough differences to warrant some extra information.

Hardware hackers may not be part of the core education focus of the Pi range, but a healthy, interested, and active hardware community that feels nurtured by its manufacturer remains key to the supply of interesting Pi-related products feeding into that market. We’d like to urge the Pi Foundation to never forget the hardware side of their ecosystem, and make hardware specification an integral part of every product launch on day one.

If the Pi 400 catches your interest, you can read our review here.