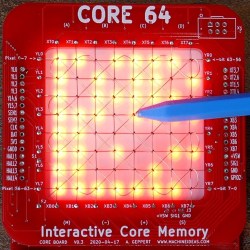

For the vast majority of us, computer memory is a somewhat abstract idea. Whether you’re declaring a variable in Python or setting a register in Verilog, the data goes — somewhere — and the rest really isn’t your problem. You may have deliberately chosen the exact address to write to, but its not like you can glance at a stick of RAM and see the data. And you almost certainly can’t rewrite it by hand. (If you can do either of those things, let us know.)

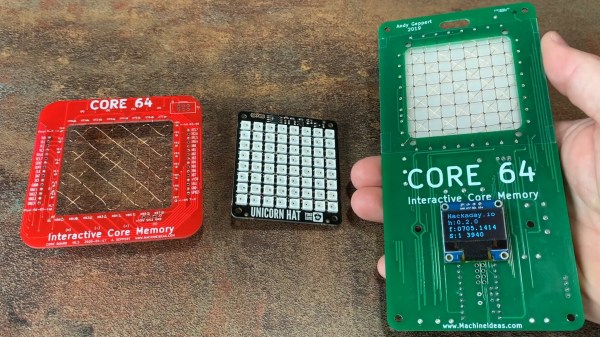

These limitations must have bothered [Andy Geppert], because he set out to bring computer memory into the  tangible (or at least, visible) world with his interactive memory badge Core 64. [Andy] has gone through a few different iterations, but essentially Core 64 is an 8×8 grid of woven core memory, which stores each bit via magnetic polarization, with a field of LEDs behind it that allow you to visualize what’s stored. The real beauty of this setup is that it it can be used to display 64 pixel graphics. Better yet — a bit can be rewritten by introducing a magnetic field at the wire junction. In other words, throw a magnet on a stick into the mix and you have yourself a tiny drawing tablet!

tangible (or at least, visible) world with his interactive memory badge Core 64. [Andy] has gone through a few different iterations, but essentially Core 64 is an 8×8 grid of woven core memory, which stores each bit via magnetic polarization, with a field of LEDs behind it that allow you to visualize what’s stored. The real beauty of this setup is that it it can be used to display 64 pixel graphics. Better yet — a bit can be rewritten by introducing a magnetic field at the wire junction. In other words, throw a magnet on a stick into the mix and you have yourself a tiny drawing tablet!

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen cool experiments with core memory, and not even the first time we’ve seen [Andy] use it to make something awesome, but it really illuminates how the technology works. Being able to not only see memory being written but to manually write to it makes it all so much realer, somehow.

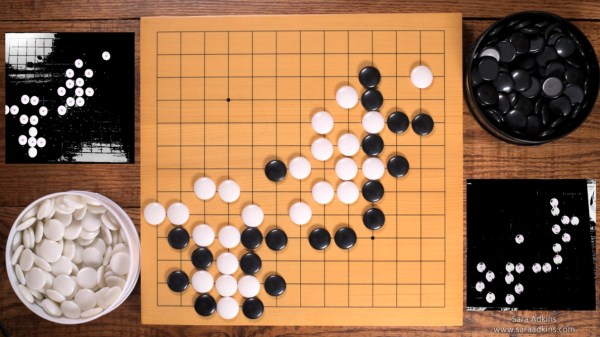

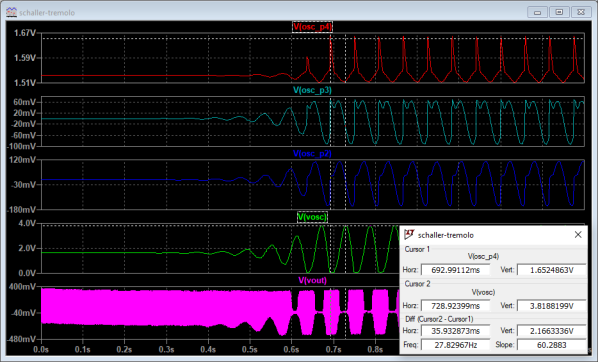

components and attenuating the low-frequency components. Of course, it’s fun to look at signals this way as well, especially when you can correlate shifts in sound quality to changes in the waveform and, ideally, the circuit that produces it.

components and attenuating the low-frequency components. Of course, it’s fun to look at signals this way as well, especially when you can correlate shifts in sound quality to changes in the waveform and, ideally, the circuit that produces it.

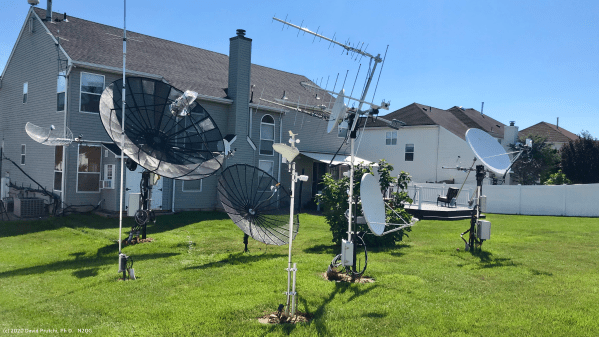

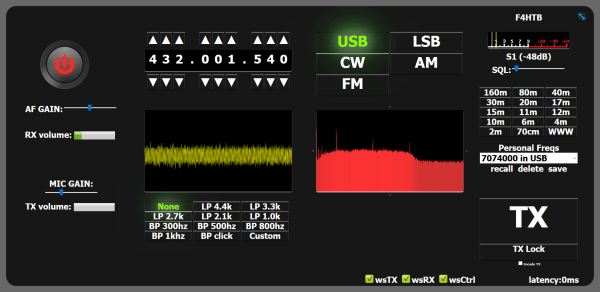

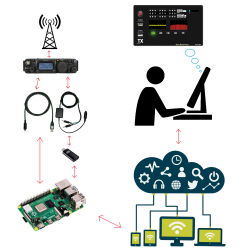

remote-controlling their rig from a laptop. As you can imagine, this essentially involves a server running on a computer hooked up to the radio, which is connected via the internet to a client running on the laptop. [Olivier/ F4HTB] saw a way to improve the process by eliminating the client software and controlling the rig from a web browser.

remote-controlling their rig from a laptop. As you can imagine, this essentially involves a server running on a computer hooked up to the radio, which is connected via the internet to a client running on the laptop. [Olivier/ F4HTB] saw a way to improve the process by eliminating the client software and controlling the rig from a web browser.