[Amen]’s Rockwell 920 calculator from the 70s was a very impressive piece of hardware for its time. It sported a 16-digit display, a printer, and it could run programs. It even had a magnetic card reader/writer that could be used to store programs and data externally. Seen through today’s eyes, it was less like a calculator and more like what we would call a single-board computer. They are also a window into another era, a time when many of the electrical design assumptions we take for granted hadn’t happened yet. When the time came to dig into what made the calculator tick, [Amen] had a lot of work to do just to get basic tools running.

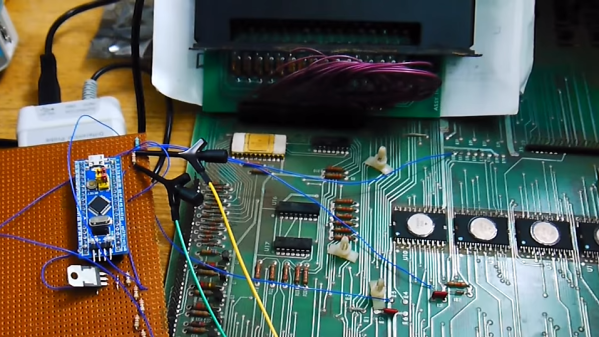

For example, [amen]’s Blue Pill (an open-source, multipurpose test and measurement tool) is, on one hand, the perfect tool to snoop on the inner workings. However, those inner workings happen to use negative logic at -17 Volts, which means a logical zero is -17 V and a one is 0 V. Oh, and it uses an oddball clock rate, to boot. Since the Blue Pill doesn’t support -17 V negative logic (does anything?) a bit of custom work was needed to craft an interface. Once that was working, the Blue Pill was off to the races.

The unfamiliar elements didn’t end there. The pins on each IC, for example, are in a staggered layout quite unlike the DIP pattern most of us (and our tools, breadboards, and IC clips) are familiar with. As for the processor itself, [amen] has access to low-level documentation on Rockwell processors and instruction sets, but the timing diagrams are puzzling until one realizes the processor has two clock inputs at two different frequencies, resulting in what [amen] describes as four separate “clock phases”.

These design decisions were certainly made for good reasons at the time, and they even have a certain internal harmony to them, but it’s still a window into an era when the elements underpinning much of what we now have and work with had not yet happened.

Check out the video embedded below to see [amen] explain what it took to hook the Blue Pill up to a Rockwell 920. Also, if you’d like to see one of these vintage machines demonstrated in all its functioning glory, here’s a video of one being put through its paces.

Continue reading “Vintage Calculator Design Shows Just How Much We Take For Granted Today”