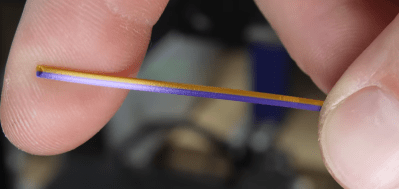

When is a line not a line? When it’s a series of tiny dots, of course!

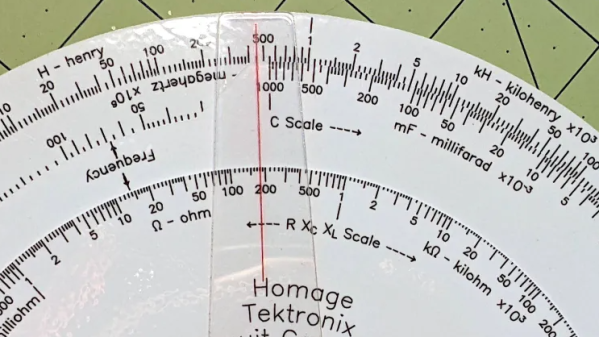

That’s the technique [Ed Nisley] used to create a super-fine, colored hairline in a piece of clear plastic — all part of his project to re-create a classic Tektronix analog calculator from the 1960s, but more on that in a moment.

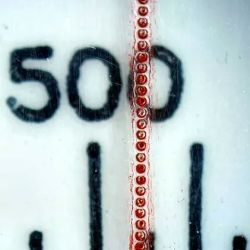

[Ed] tried a variety of methods and techniques, including laser engraving a solid line, and milling a line with an extremely tiny v-tool. Results were serviceable, but what really did the trick was a series of tiny laser-etched craters filled in with a red marker. That resulted in what appears — to the naked eye — as an extremely fine hairline. But when magnified, as shown here, one can see it is really a series of small craters. The color comes from coloring in the line with a red marker, then wiping the excess off with some alcohol. The remaining pigment sitting in the craters gives just the right amount of color.

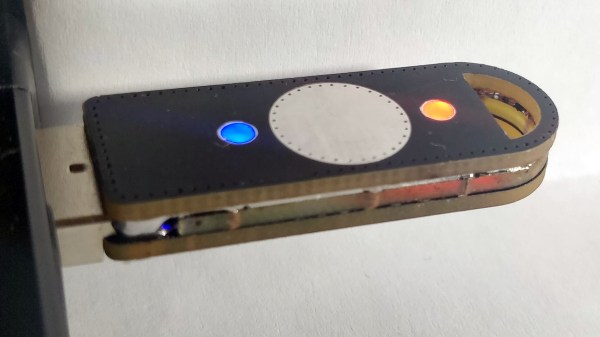

This is all part of [Ed]’s efforts to re-create the Tektronix Circuit Computer, a circular slide rule capable of calculating all kinds of useful electrical engineering-related things. And if you find yourself looking to design and build your own circular slide rule from scratch? We have you covered.