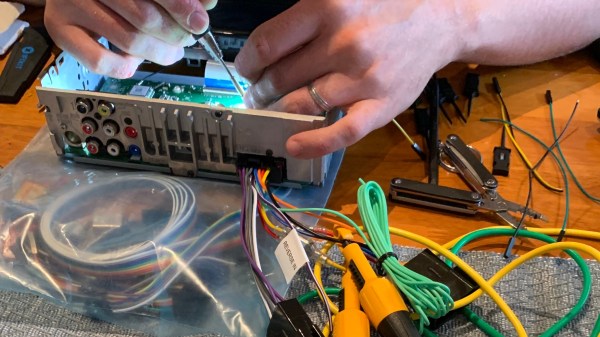

Even spendy commercial products can end up being lemons. This is something [Mike Buss] is familiar with, as he had the misfortune of being stuck using what he declares is the world’s worst USB hub, and it’s not even a mystery discount device from overseas: it’s an HP Thunderbolt Dock G2. It is a sort of combination I/O dock and USB hub, and it caused him no end of frustration until he “fixed” it with a crude workaround.

The problems with [Mike]’s dock come down to two major issues. The first is that the USB-C connection will, if moved even the slightest amount, instantly trigger a disconnect from the host computer. Frankly, that sounds like a defect, but that’s not all. The other issue is that the whole top of the device is actually a giant, hyper-sensitive button. Even a stern gaze seems to be enough to cause it to activate. What does the button do? It puts the host computer to sleep; something that we all agree should suffer from as few false activations as possible.

We’ll spoil the surprise by revealing that the “fix” was nothing more than putting a 3D printed enclosure around the troublesome device, as shown in the image above. Keeping the dock covered and perfectly still at least prevents the two aforementioned issues, and that’s good enough for [Mike].

The curious part of all this is just how badly the device’s design affected normal use. We’d suspect a defect or malfunction, but a cursory search of reviews online suggests [Mike]’s experience isn’t unique. It’s certainly not the first poorly-designed product we’ve seen fixed by a new enclosure, but some problems just aren’t worth the effort of a more elegant solution.