We are living in great times for DIY, although ironically some of that is because of all the steps that we don’t have to do ourselves. PCBs can be ordered out easily and inexpensively, and the mechanical parts of our projects can be ordered conveniently online, fabricated in quantity one for not much more than a song, or 3D printed at home when plastic will do. Is this really DIY if everything is being farmed out? Yes, no, and maybe.

It all depends on where you think the real value of DIY lies. Is it in the idea, the concept, the design? Or in its realization, the manufacturing? I would claim that most of the value actually lies in the former, as much as I personally enjoy the many processes of physically constructing the individual parts of many projects.

For instance, I designed and built a hot-wire CNC foam cutter recently. Or better, I designed a series of improved versions, because I never get anything right on the first try. All along the way, I 3D printed new and improved versions of the plastic parts, ironing as many of the little glitches out as I had patience for. This took probably a good handful of weekends’ time, spread out over a couple months, but in comparison to time spent testing, fixing, and redesigning, very little time or effort was spent in the physical building.

Moreover, I bought most of the parts at the hardware store. The motor controller shield and cheap Arduino clone came from eBay. And even those that I did manufacture myself, the 3D-printed bits, were kind of made by a machine — my experience of the whole process wouldn’t have been any different if I ordered them out.

Of course craftsmanship still exists, and we see that in Hackaday projects all the time. Heck, I’ll admit that I still enjoy a lot of the process of making things with my own hands for its own sake. It’s peaceful. But if there’s one thing that the rapid proliferation of ideas and projects that have been facilitated by 3D printing and cheap short-run PCB services, it’s that the real value of many projects lies in the idea, and the documentation. Which is to say, I gotta get around to writing up that foam cutter…

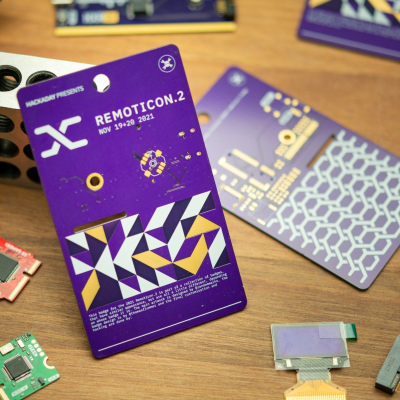

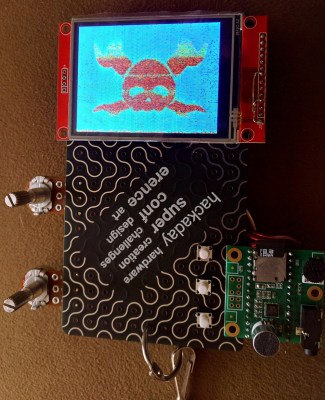

Here’s one extreme solution: the badge at the first Supercon. Faced with essentially zero budget and a tight time constraint, the Hackaday team punted — and produced a prototype board, but had tons of parts on hand for everyone to draw from. And

Here’s one extreme solution: the badge at the first Supercon. Faced with essentially zero budget and a tight time constraint, the Hackaday team punted — and produced a prototype board, but had tons of parts on hand for everyone to draw from. And