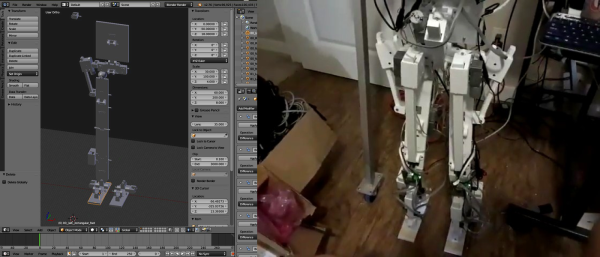

If you’re working on your own bipedal robot, you don’t have to start from the ground up anymore. [Ted Huntington]’s Two Leg Robot project aims to be an Open Source platform that’ll give any future humanoid-robot builders a leg up.

While we’ve seen quite a few small two-legged walkers, making a pair of legs for something human-sized is a totally different endeavor. [Ted]’s legs are chock-full of sensors, and there’s a lot of software that processes all of the data. That’s full kinematics and sensor info going back and forth from 3D model to hardware. Very cool. And to top it all off, “Two Leg” uses affordable motors and gearing. This is a full-sized bipedal robot platform that you might someday be to afford!

Will walking robots really change the world? Maybe. Will easily available designs for an affordable bipedal platform give hackers of the future a good base to stand on? We hope so! And that’s why this is a great entry for the Hackaday Prize.