Back in 2016, Hackaday published a review of The National Museum of Computing, at Bletchley Park. It mentions among the fascinating array of computer artifacts on display a single box that could be found in the corner of a room alongside their Cray-1 supercomputer. This was a Transputer development system, and though its architecture is almost forgotten today there was a time when this British-developed microprocessor family had a real prospect of representing the future of computing. So what on earth was the Transputer, why was it special, and why don’t we have one on every desk in 2019?

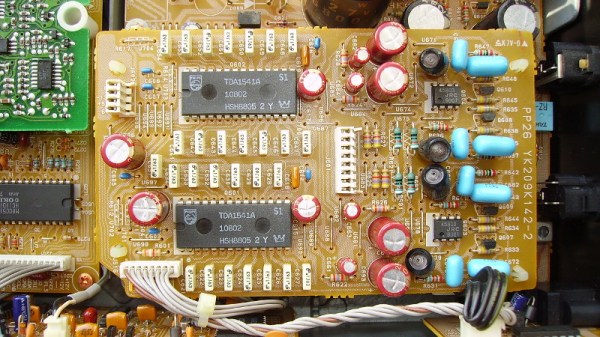

![An Inmos RAMDAC (the 28-pin DIP) on the motherboard of a 1989 IBM PS/55. Darklanlan [CC BY 4.0]](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/ibm_vga_90x8941_on_ps55.jpg?w=400)

This microprocessor family addressed the speed bottlenecks inherent to conventional processors of the day by being built from the ground up to be massively multiprocessor. A network of Transputer processors would share a web of serial interconnects arranged in a crosspoint formation, allowing multiple of them to connect with each other independently and without collisions. It was the first to feature such an architecture, and at the time was seen as the Next Big Thing. All computers were going to use Transputers by the end of the 1990s, so electronic engineering students were taught all about them and encountered them in their group projects. I remember my year of third-year EE class would split into groups, each of tasked with a part of a greater project that would communicate through the crosspoint switch at the heart of one of the Transputer systems, though my recollection is that none of the groups went so far as to get anything to work. Still how this machine was designed is fun to look back on in modern times. Let’s dig in!