If you were to invent a time machine and transport a typical hardware hacker of the 1970s into 2018 and sit them at a bench alongside their modern counterpart, you’d expect them to be faced with a pile of new things, novel experiences, and exciting possibilities. The Internet for all, desktop computing fulfilling its potential, cheap single-board computers, even ubiquitous surface-mount components.

What you might not expect though is that the 2018 hacker might discover a whole field of equivalent unfamiliarity while being very relevant from their grizzled guest. It’s something Scott Swaaley touches upon in his Superconference talk: “Lessons Learned in Designing High Power Line Voltage Circuits” in which he describes his quest for an electronic motor brake, and how his experiences had left him with a gap in his knowledge when it came to working with AC mains voltage.

When Did You Last Handle AC Line voltages?

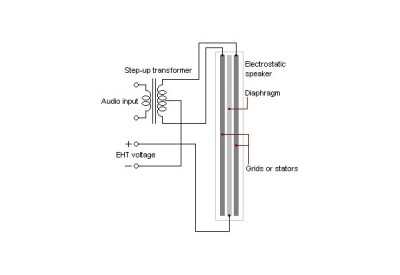

If you think about it, the AC supply has become something we rarely encounter for several reasons. Our 1970s hacker would have been used to wiring in mains transformers, to repairing tube-driven equipment or CRT televisions with live chassis’, and to working with lighting that was almost exclusively provided by mains-driven incandescent bulbs. A common project of the day would have been a lighting dimmer with a triac, by contrast we work in a world of microcontroller-PWM-driven LEDs and off-the-shelf switch-mode power supplies in which we have no need to see the high voltages. It may be no bad thing that we are rarely exposed to high-voltage risk, but along the way we may have lost a part of our collective skillset.

Scott’s path to gaining his mains voltage experience started in a school workshop, with a bandsaw. Inertia in the saw kept the blade moving after the power had been withdrawn, and while that might be something many of us are used to it was inappropriate in that setting as kids are better remaining attached to their fingers. He looked at brakes and electrical loads as the solution to stopping the motor, but finally settled on something far simpler. An induction motor can be stopped very quickly indeed by applying a DC voltage to it, and his quest to achieve this led along the path of working with the AC supply. Eventually he had a working prototype, which he further developed to become the MakeSafe power tool brake.

Get Your AC Switching Right First Time

The full talk is embedded below the break, and gives a very good introduction to the topic of switching AC power. If you’ve never encountered a thryristor, a triac, or even a diac, these once-ubiquitous components make an entrance. We learn about relays and contactors, and how back EMF can destroy them, and about the different strategies to protect them. Our 1970s hacker would recognise some of these, but even here there are components that have reached the market since their time that they would probably give anything to have. We see the genesis of the MakeSafe brake as a panel with a bunch of relays and an electronic fan controller with a rectifier to produce the DC, and we hear about adequate safety precautions. This is music to our ears, as it’s a subject we’ve touched on before both in terms of handling mains on your bench and inside live equipment.

So if you’ve never dealt with AC line voltages, give this talk a look. The days of wiring up transformers to power projects might be largely behind us, but the skills and principles contained within it are still valid.

Continue reading “Scott Swaaley On High Voltage” →

![The hydrogen-powered Honda Clarity FCV, a car most of us will probably never see. Lcaa9 [CC BY-SA 4.0].](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/1024px-2018_honda_clarity_fuel_cell.jpg?w=400)