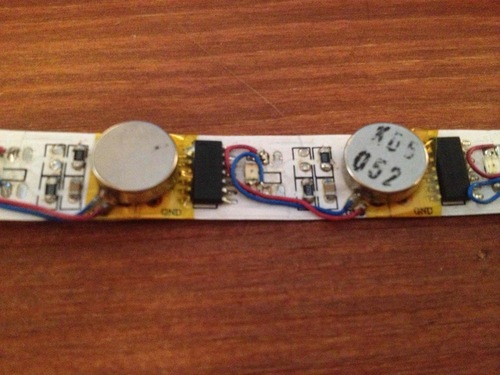

nRF24L01+ modules like the one shown above are a great way to send data wirelessly between your projects. They can be found on many websites for less than $1.50 a piece and many libraries exist for them. After having thoroughly looked at the Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) specifications, [Dimitry] managed to find a way to broadcast BLE data with an nRF24L01+.

Luckily enough, BLE and nRF24L01+ data packets have the same preambles. However, the latter can’t send more than 32 bytes in a packet and can’t hop between frequencies as fast as the BLE specification wants. [Dimitry] found the solution when he discovered that he could send unsolicited advertisements on three specific channels. In the end, considering the 32 bytes the nRF24L01+ can send, you’ll need to use 3 bytes for the CRC, 2 for the packet header, 6 for the MAC address and 5 for devices attributes. This leaves us with 16 bytes of pure data or 14 bytes to split between data and name if you want your project to have one.