Laptop computers may be ubiquitous today, but there was a time when they were the exclusive preserve of rich businesspeople. Back in the early ’90s, the significant added cost of portability was something that few were willing to pay. As a result, not many laptops from those days survive; for those that do, keeping them running can be quite a challenge due to their compact construction and use of non-standard components.

[Adalbert] ran into these problems when he got his hands on a Toshiba T3200SXC from 1991. As the first laptop ever to feature a color TFT display, it’s very much worth preserving as an historical artifact. Sadly, the original display was no longer working: it only displayed a very faint image and went completely blank soon after. Leaky capacitors then destroyed the power supply board, leaving the laptop completely dead. [Adalbert] then began to ponder his options, which ranged from trying to repair the original components to ripping everything out and turning this into a modern-computer-in-an-old-case project.

In the end he went for an option in between, which we as preservationists can only applaud: he replaced the display with a modern one of the correct size and resolution and built a new custom power supply, keeping the rest of the computer intact as far as possible. [Adalbert] describes the overall process in the video embedded below and goes into lots of detail on his hackaday.io page.

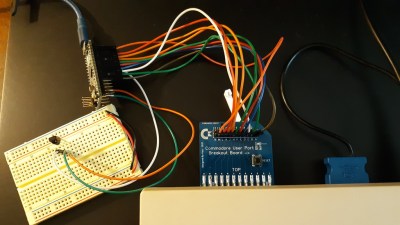

Connecting a modern LCD screen was not as difficult as it might seem: where the old display had an RGB TTL interface with three bits per color, the new one had a very similar system with six bits per color. [Adalbert] made an adapter PCB that simply connected the three bits from the laptop to the highest three bits on the screen. A set of 3D-printed brackets ensured a secure fit of the new screen in the classic case.

For the power supply [Adalbert] took a similar approach. He designed a PCB with several DC/DC converters that fit easily inside the computer’s case, leaving enough space to add a battery. This made the old Toshiba more portable than it ever was — believe it or not, the original T3200SXC could only be used with a mains connection.

For the power supply [Adalbert] took a similar approach. He designed a PCB with several DC/DC converters that fit easily inside the computer’s case, leaving enough space to add a battery. This made the old Toshiba more portable than it ever was — believe it or not, the original T3200SXC could only be used with a mains connection.

Once the laptop was restored to working order, [Adalbert] added a few finishing touches: a sound card and speakers made it suitable as a gaming platform, and a network card gave it rudimentary online capabilities. The end result is a T3200SXC that looks and feels exactly the way it did when it was new, but with a few added features. That’s a really satisfying result: many classic laptop projects add modern computing hardware, or even completely replace the original contents. You might also want to check out [Adalbert]’s unusual 3D printer based PCB manufacturing technique that he used for the new power supply.

Continue reading “Hackaday Prize 2022: Repairing A Vintage Laptop With Modern Components”