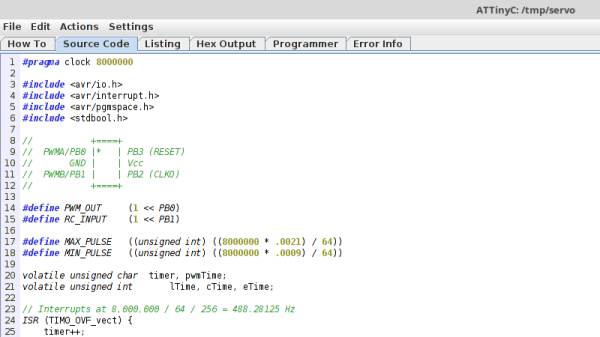

When writing code for the ATtiny family of microcontrollers such as a the ATtiny85 or ATtiny10, people usually use one of two methods: they either add support for the chip in the Arduino IDE, or they crack open their text editor of choice and do everything manually. Plus of course there are the stragglers out there using Eclipse. But [Wayne Holder] thinks there’s a better way.

The project started out as a simple way for [Wayne] to program the ATtiny10 in C under Mac OS, but has since evolved into an open source, cross-platform integrated development environment (IDE) for programming a wide range of ATtiny chips in C, C++, or Assembly. Not only does it integrate the source code editor and programmer, but it even bundles in documentation for common variants of the chips including block diagrams and pinouts; making it a true one-stop-shop for ATtiny hacking.

The project started out as a simple way for [Wayne] to program the ATtiny10 in C under Mac OS, but has since evolved into an open source, cross-platform integrated development environment (IDE) for programming a wide range of ATtiny chips in C, C++, or Assembly. Not only does it integrate the source code editor and programmer, but it even bundles in documentation for common variants of the chips including block diagrams and pinouts; making it a true one-stop-shop for ATtiny hacking.

His IDE runs under Java, including OpenJDK, and [Wayne] provides a stable pre-built executable for those who don’t want to clone the whole GitHub repository. He’s included the GNU/AVR toolchains, though notes that testing so far has been limited to Mac OS, and he’s interested in feedback from Windows and Linux users. Assembly is done either with GNU AVR-AS, or an assembler of his own design, though the latter is currently limited to the ATTiny10.

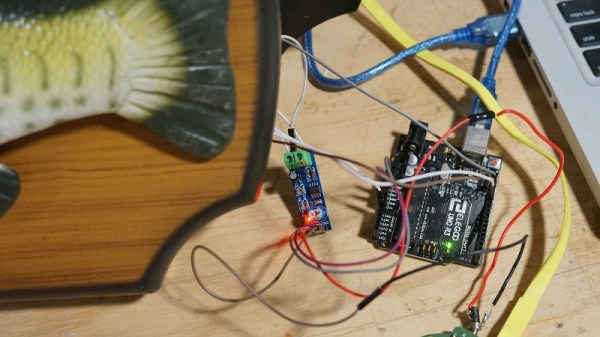

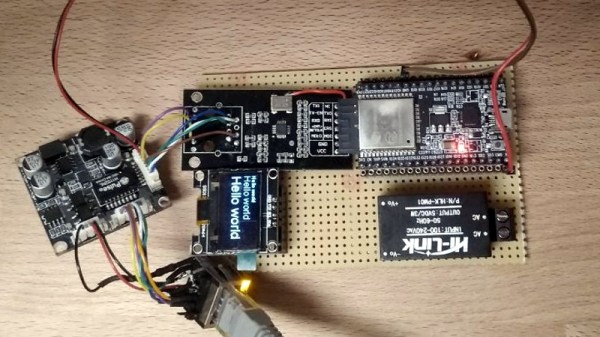

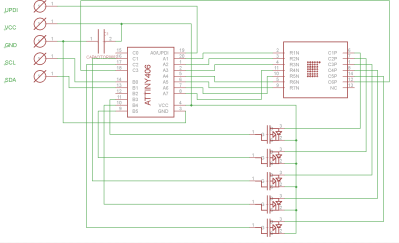

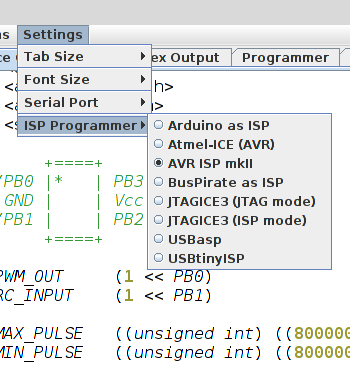

To actually get the code onto the chip, the IDE supports using the Arduino as a programmer as well as dedicated hardware like the BusPirate or the USBasp. If you go the Arduino route, [Wayne] has even come up with a little adapter board which he’s made available through OSH Park to help wrangle the diminutive chips.

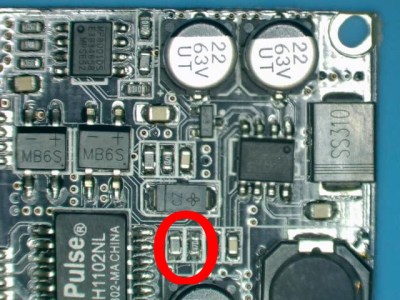

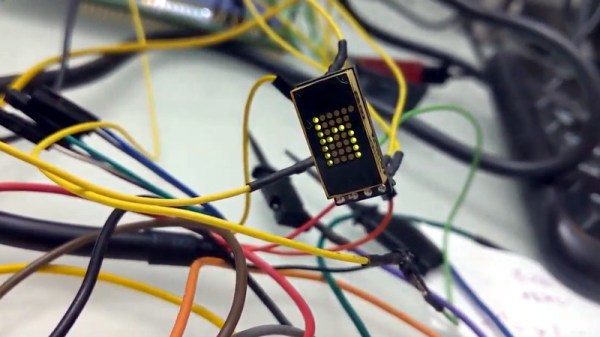

The ATtiny10 might have something of a learning curve, but in exchange this family of tiny microcontrollers offers an incredible amount of capability. When you’re working with what’s essentially a programmable grain of rice, the only limit is your own creativity.