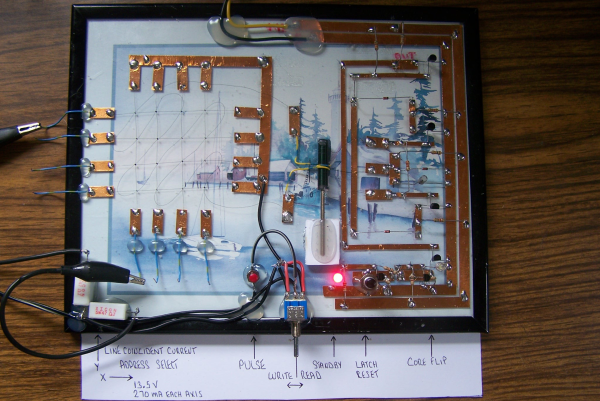

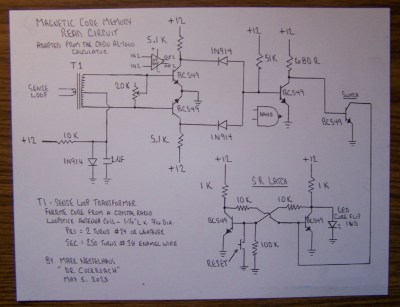

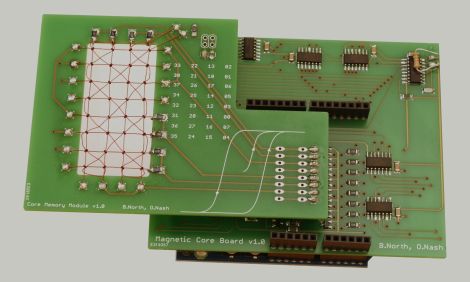

Magnetic Core memory was the RAM at the heart of many computer systems through the 1970s, and is undergoing something of a resurgence today since it is easiest form of memory for an enterprising hacker to DIY. [Han] has an excellent writeup that goes deep in the best-practices of how to wire up core memory, that pairs with his 512-bit MagneticCoreMemoryController on GitHub.

Magnetic core memory works by storing data inside the magnetic flux of a ferrite ‘core’. Magnetize it in one direction, you have a 1; the other is a 0. Sensing is current-based, and erases the existing value, requiring a read-rewrite circuit. You want the gory details? Check out [Han]’s writeup; he explains it better than we can, complete with how to wire the ferrites and oscilloscope traces to explain why you want to wiring them that way. It may be the most complete design brief to be written about magnetic core memory to be written this decade.

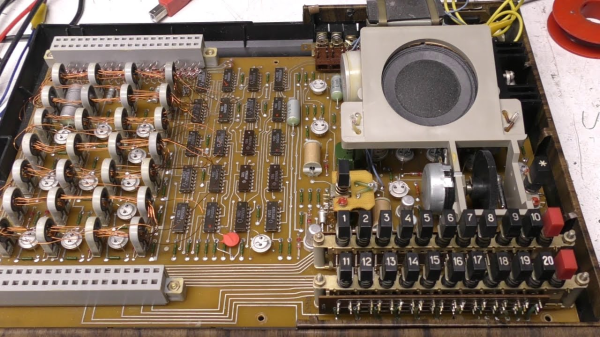

This little memory pack [Han] built with this information is rock-solid: it ran for 24 hours straight, undergoing multiple continuous memory tests — a total of several gigabytes of information, with zero errors. That was always the strength of ferrite memory, though, along with the fact you can lose power and keep your data. In in the retrocomputer world, 512 bits doesn’t seem like much, but it’s enough to play with. We’ve even featured smaller magnetic core modules, like the Core 64. (No prize if you guess how many bits that is.) One could be excused for considering them toys; in the old days, you’d have had cabinets full of these sorts of hand-wound memory cards.

Magnetic core memory should not be confused with core-rope memory, which was a ROM solution of similar vintage. The legendary Apollo Guidance Computer used both.

We’d love to see a hack that makes real use of these pre-modern memory modality– if you know of one, send in a tip.

tangible (or at least, visible) world with his

tangible (or at least, visible) world with his

Peek behind the polished face and you’ll find a mechanical sleight of hand. This isn’t your grandfather’s gear-laden

Peek behind the polished face and you’ll find a mechanical sleight of hand. This isn’t your grandfather’s gear-laden