[Evan] couldn’t find a phone he liked, so he decided to build his own. There are advantages and disadvantages, as you might expect. On the plus side, you have the ultimate control. On the negative side, it doesn’t quite have the curb appeal — at least to the average user — of a sleek new cell phone from a major manufacturer.

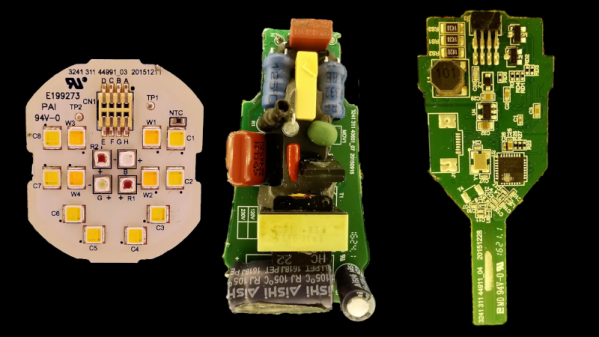

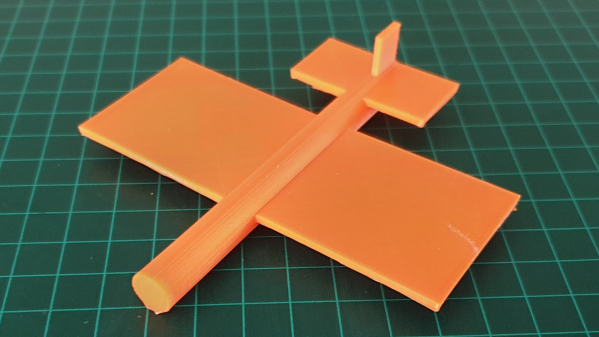

The phone uses a Raspberry Pi, along with a 4G modem and a 480×800 touchscreen. There’s a laser cut box that measures 90x160x30 mm. For reference, a Google Pixel 7 is about 73x156x9 mm, so a little easier on the pocket.

But not one the pocketbook. The OURPhone only costs about $200 USD to build. There are trade-offs. For example, the touchscreen is resistive, so you’ll want a stylus (there’s a slot for it in the case). On the other hand, if you don’t like something, it is all there for you to change.

Obviously, a better screen would help. Thinner batteries might be a good enhancement too. But that’s the beauty of an open project. You can do all these things and more.

We wondered if you could get one of the “mobile” Linux editions to run or even Android. It seems like the hardest part is coming up with a sophisticated enclosure.